Artificial intelligence runs on computation.

Computation runs on electricity.

Electricity, at scale, now runs on batteries.

At the center of this chain sits lithium — and increasingly, Zimbabwe. The country is definitely exporting the infrastructure of AI.

Zimbabwe produced approximately 280,000 metric tons of lithium concentrate in 2023, making it Africa’s largest producer and the world’s fourth-largest supplier.

In 2024, the country accounted for 80% of Africa’s total lithium output, driven by more than $1.4 billion in Chinese investment.

With estimated reserves exceeding 500,000 tons of lithium metal, the country has become a critical node in the global transition toward battery-powered systems that underpin electric vehicles, renewable energy grids, and the physical infrastructure of AI.

The lithium beneath Zimbabwe’s soil is no longer just about cars or phones. It is about who can store power, stabilize grids, and host compute-intensive technologies. The question is whether Zimbabwe will remain a raw material exporter or build the infrastructure that lithium itself enables.

Zimbabwe’s Bikita lithium mine

Why Lithium Is Strategic to the AI Era

Lithium-ion batteries store over 90% of grid-scale renewable energy worldwide (International Energy Agency, 2024). This is no longer a clean energy story — it is a computation story.

A typical hyperscale data center requires 40–100 MWh of battery backup to prevent downtime during grid fluctuations. AI workloads are especially power-sensitive: industry estimates suggest a single second of downtime at a major data center can cost $100,000–300,000. Google’s facilities maintain a 99.99% uptime requirement — achievable only with sophisticated battery backup systems.

Global lithium demand is projected to reach 3.3 million tons by 2030, driven by energy storage (42%) and electric vehicles (38%) (BloombergNEF, 2024). AI infrastructure growth is accelerating this timeline. Microsoft alone has committed to 10.5 GW of new data center capacity by 2026, each gigawatt requiring approximately 100–150 MWh of lithium battery storage.

Lithium is no longer peripheral to technology infrastructure. It is central.

Zimbabwe’s Lithium Endowment

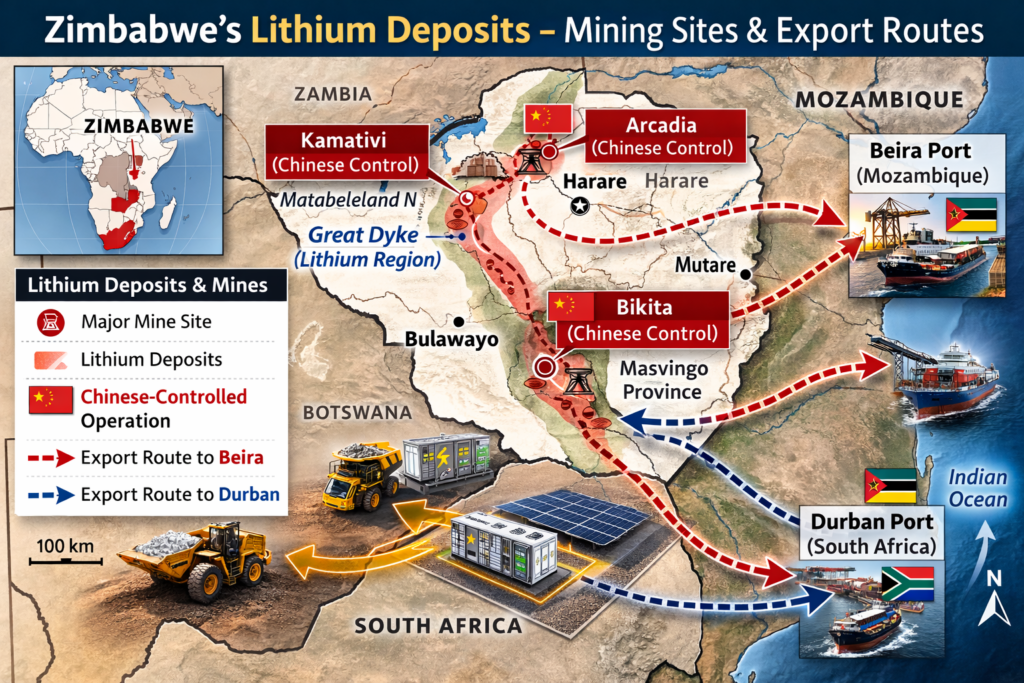

Zimbabwe’s lithium deposits are concentrated in the mineral-rich Great Dyke geological formation, stretching 550 kilometers through the country’s center. Hard-rock spodumene deposits contain lithium concentrations of 1.0–1.5% Li₂O, comparable to Australia’s quality but with significantly lower extraction costs due to accessible open-pit mining conditions.

Key Deposits

- Bikita: One of the world’s oldest lithium mines, producing since 1950

- Arcadia: 79.4 million tons of ore reserves with 1.22% lithium oxide

- Kamativi: Historical producer being revived with Chinese investment

Zimbabwe’s advantage is both geological and temporal: while brine deposits in Chile and Argentina require 12–18 months of evaporation processing, hard-rock extraction can reach market within 3–6 months. In a supply-constrained world, this speed creates strategic value.

Dark streets during load-shedding in Harare and a battery storage facility. Zimbabwe’s lithium could power domestic storage systems but currently leaves the country as raw concentrate

The Domestic Power Paradox

Zimbabwe’s central contradiction: it exports materials that store electricity while experiencing chronic power deficits. The gap between resource wealth and energy access is structural, not incidental.

The scale of the mismatch:

- Zimbabwe’s installed generation capacity: ~2,200 MW

- Actual available power (2023 average): ~1,100 MW

- Demand: ~2,100 MW

- Daily load-shedding: 8–12 hours in urban areas, 16+ hours rural

The economic cost:

- Manufacturing operates at 40–60% capacity utilization

- Telecommunications companies spend 30% of operating budgets on diesel generators

- Data centers are virtually nonexistent outside Harare

- Digital economy remains constrained to low-bandwidth, low-compute services

A single 50 MWh battery storage facility — requiring approximately 4,000 tons of lithium carbonate — could stabilize power for a 100,000-person district, enabling productive hours currently lost to outages.

Zimbabwe produced enough lithium in 2023 to theoretically build 7 GWh of battery storage — enough to provide 3–4 hours of backup power for the entire national grid.

Instead, that lithium left the country as concentrate, was refined in China, manufactured into batteries in South Korea, and reimported as diesel generator replacements at 10–15× the value of the original export. This is not just an economic inefficiency. It is a strategic vulnerability.

The Digital Sovereignty Paradox

Zimbabwe is participating in a structural misalignment, exporting the raw materials required to stabilize its own economy. By exporting lithium while the domestic grid fails, the nation is surrendering the economic agency to power its own industrial and AI future.

The metrics of dependency:

- Resource outflow: ~100% of battery-grade lithium concentrate is currently exported, optimized for foreign grids while Zimbabwe’s industrial base experiences chronic power shortages

- Productivity cost: Estimated $2.1 billion annual GDP loss due to power-related manufacturing downtime (World Bank Zimbabwe Manufacturing Capacity Utilization Report, 2023)

- Import markup: Zimbabwean businesses pay 10–15× price markups to re-import their own minerals as finished battery systems

- Computation deficit: 0.0% availability of domestic, battery-backed hyperscale compute infrastructure. Zimbabwe mines the materials for AI infrastructure but cannot host it

The current model represents voluntary energy insolvency. Every ton of spodumene that leaves Beira or Durban without a domestic retention agreement for local storage is a lost opportunity to bridge the 1,000 MW demand gap that constrains startups, hospitals, and manufacturing facilities.

The 0.0% domestic compute availability is not a technical limitation — it is a policy choice. Zimbabwe possesses the raw materials to build battery-backed data infrastructure but exports them before they can serve domestic needs.

True economic agency is measured in kilowatt-hours, not mining licenses. Until Zimbabwe mandates that a portion of its mineral wealth be converted into domestic energy storage infrastructure, it will remain a spectator in the AI transformation it is helping to build.

The pathway out of this structural misalignment requires a deliberate policy shift — one that treats lithium not as an export commodity but as domestic infrastructure.

The Supply Chain Reality

Zimbabwe occupies the lowest-value segment of a seven-stage chain, capturing approximately $40–60 in value for every $1,000 of battery product sold globally.

The Battery Value Chain

| Stage | Activity | Key Players / Location | Price / Output | Value Capture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Mining | Zimbabwe | $800–1,200 / ton (spodumene concentrate) | 5% |

| Stage 2 | Concentration | — | Upgraded to chemical-grade concentrate | 3% |

| Stage 3 | Refining | China (70% global capacity) | $15,000–25,000 / ton (Li carbonate / hydroxide) | 15% |

| Stage 4 | Cathode Production | China, Japan, South Korea | $35,000–50,000 / ton (cathode materials) | 25% |

| Stage 5 | Cell Manufacturing | China (75% global capacity) | $80–120 / kWh (battery cells) | 30% |

| Stage 6 | Pack Assembly | — | $150–200 / kWh (complete systems) | 12% |

| Stage 7 | Integration & Deployment | — | Energy storage systems, EVs, backup power | 10% |

Zimbabwe’s lithium deposits in the Great Dyke region, mining sites, and export routes

Chinese Integration: Speed Without Diversification

Six Chinese companies now control approximately 80% of Zimbabwe’s lithium production. Their vertical integration delivers speed — capital deployment in 18–24 months from license to production, guaranteed offtake before mining begins. But it concentrates risk.

Key operators: Sinomine (Bikita mine, ~120,000 tons/year), Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt (Arcadia project, integrated into CATL supply chain), Canmax, Chengxin Lithium, Yahua, and Tsingshan (multiple exploration and revival projects).

What Zimbabwe Has Gained

- Rapid capital deployment ($2B+ since 2021)

- Speed to market — concentrate flowing within 18–24 months

- Employment at extraction level

- Infrastructure improvements at mine sites

The Structural Limitations

- ~95% of exports flow to a single buyer (China)

- Bilateral pricing often below spot market rates

- No alternative buyers to leverage for better terms

- Technology transfer minimal

Zimbabwe has become a reliable, high-speed supplier to a single customer. Speed has increased. Value capture and strategic optionality have not.

A Concrete Pathway: The Three-Horizon Strategy

Rather than attempting to capture all seven value chain stages simultaneously — which would be capital-intensive, technically demanding, and politically complex — Zimbabwe could pursue a sequenced approach targeting specific segments where competitive advantages already exist.

Horizon 1: 2025–2027: Domestic Energy Storage Deployment

Objective: Retain 5–10% of lithium production for domestic battery storage systems

Mechanism: Require mining companies to allocate 5% of production to domestic projects at cost plus 20% margin. Deploy 200–300 MWh of grid-scale storage at 6–8 strategic substations. Install 50–100 MWh of distributed storage at telecommunications hubs, hospitals, and agricultural processing facilities.

Impact: Reduce load-shedding by 30–40% in targeted areas, enable 24/7 operations for critical infrastructure, create immediate market for assembly skills, demonstrate domestic use case for lithium.

$150–200MInvestment Required

400–600Jobs Created

30–40%Load-shedding Reduction

Horizon 2: 2027–2030: Regional Battery Assembly Hub

Objective: Establish Southern Africa’s first lithium battery assembly facility

Target: Production of 1–2 GWh/year of assembled battery packs for regional telecom operators (DRC, Zambia, Mozambique spend $800M/year on diesel backup), mining operations (40% of Southern African mining uses diesel generators), agricultural cold chain storage, and municipal microgrids.

Model: Partnership with established cell manufacturer (LG Energy Solution, Samsung SDI, or second-tier Chinese firms seeking supply chain diversification). Import cells, conduct pack assembly and battery management system integration. Focus on stationary storage — simpler than EV batteries, longer product cycles, larger regional demand.

Competitive advantages: Proximity to lithium source, lower labor costs than Asian manufacturing, regional market access (SADC, COMESA), avoided transport costs for Southern African customers.

$300–500MInvestment Required

1,200–1,800Jobs Created

15–20%Value Chain Capture

Horizon 3: 2030–2035: Lithium Refining Capacity

Objective: Produce battery-grade lithium carbonate or hydroxide

Scale: 20,000–30,000 tons/year lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE)

Rationale: By 2030, domestic assembly creates local demand for refined lithium. Refining captures additional 15% of value chain. Reduces dependence on Chinese processing monopoly. Creates feedstock for potential future cathode production.

Critical success factors: Reliable electricity (battery storage from Horizon 1 enables this), technical expertise (partnership with Australian, Chilean, or Canadian refiners), environmental controls, long-term offtake agreements.

$400–600MInvestment Required

600–900Jobs Created

+15%Additional Value

Why This Pathway Works

This three-horizon approach is sequenced to overcome Zimbabwe’s current constraints:

- It starts with domestic demand: Energy storage solves Zimbabwe’s own power crisis while creating a visible use case and skilled workforce

- It builds on regional demand: Southern Africa’s infrastructure gaps create immediate markets for assembled batteries without competing against Asian manufacturers in oversupplied EV markets

- It delays capital-intensive stages: Refining comes last, after domestic assembly creates guaranteed demand and revenue streams to support investment

- It accepts partial value capture: Moving from 5% to 20–25% of the value chain is realistic and transformative — full vertical integration is unnecessary and likely uncompetitive

Precedent: Indonesia’s Nickel Strategy

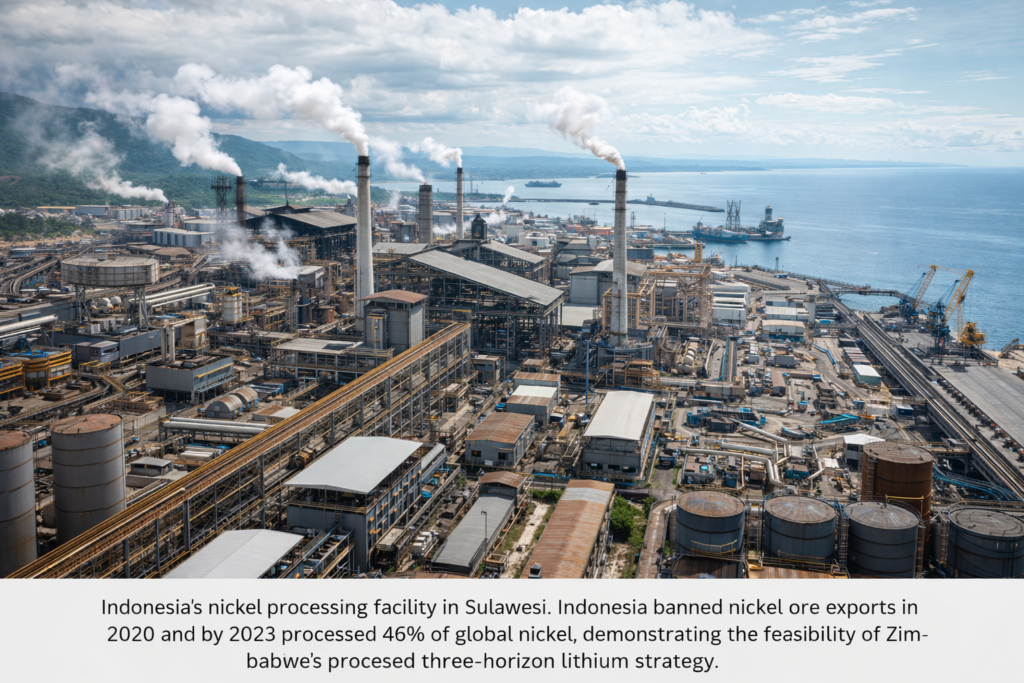

Indonesia executed a similar strategy with nickel, banning ore exports in 2020 and attracting $30 billion in processing investments. By 2023, Indonesia processed 48% of global nickel (up from 12% in 2019) and captured significantly more value per ton extracted (UNCTAD Critical Minerals Brief, 2024).

Governance and Standards: Competing on Reliability

As lithium demand outstrips supply, global buyers face a strategic choice: secure volume at any cost, or build resilient, responsible supply chains. Western manufacturers — Tesla, BMW, Volkswagen — are under increasing pressure to audit sourcing. Certification programs like the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance and Responsible Minerals Initiative are creating price premiums of 5–15% for traceable, certified supply.

Zimbabwe can differentiate on more than speed:

- Environmental performance: Hard-rock mining in Zimbabwe uses 40–60% less water than South American brine operations. With 330 days of sunlight annually, Zimbabwe has potential for solar-powered processing facilities

- Supply chain transparency: Mine-to-battery certification yields 5–15% price premium with Western buyers seeking alternatives to opaque supply chains

- Community engagement: Transparent benefit-sharing mechanisms build long-term social license and contrast with contentious artisanal mining conditions in neighboring markets

The choice is not between Chinese investment and Western investment. It is between being a commodity supplier to any buyer, or a strategic partner to buyers who value reliability, ethics, and long-term relationships. Both paths provide revenue. Only one provides leverage.

A hyperscale data center

Batteries as the Hidden Enabler of AI Infrastructure

Data centers represent the fastest-growing electricity load globally, projected to consume 8% of total global power by 2030 — up from 1% in 2020 (IEA Data Centers and Data Transmission Networks Report, 2024). AI accelerates this trajectory in three ways that depend directly on batteries:

- Grid balancing: AI facilities locate near cheap renewable energy — solar and wind — requiring 1–3 hours of storage to smooth intermittency

- Backup power: Unlike traditional IT, AI training runs cannot pause without losing days of computational progress — battery backup is mandatory, not optional

- Demand response: Batteries allow data centers to shift consumption to low-demand periods, reducing infrastructure costs by 30–40%

Zimbabwe’s lithium is already enabling AI infrastructure — in Virginia, Singapore, and Stockholm. The question is whether any of that enabling infrastructure will be built in Harare, Bulawayo, or Lusaka.

Regional opportunity: East Africa’s data center market is projected to grow 15% annually through 2030. Currently, 90% of Africa’s data is stored outside the continent due to power unreliability.

A 50 MW data center requires approximately 100–150 MWh of battery storage — equivalent to the lithium output from a mid-sized Zimbabwean mine operating for 3–4 months.

Battery-backed infrastructure could enable regional data sovereignty and lower-latency services for 600 million East and Southern Africans — a foundation for domestic AI development.

The Choice Ahead

Zimbabwe currently operates as a lithium supplier: extracting resources, exporting concentrate, importing finished goods. The three-horizon strategy would transform Zimbabwe into an infrastructure enabler: deploying the technologies its minerals make possible.

The difference matters.

Suppliers compete on volume and price — a race to the bottom as new deposits come online in Mali, DRC, and Nigeria. Enablers compete on capability and reliability — building infrastructure that anchors long-term industrial development.

What success looks like by 2035:

- Zimbabwe’s grid stabilized by 2–3 GWh of domestic battery storage

- 40–50% reduction in load-shedding enables manufacturing renaissance

- Regional battery assembly hub employing 2,000+ workers supplies Southern African infrastructure projects

- Lithium refining capacity reduces export of raw concentrate from 95% to 60%

- Value captured per ton of lithium increases from $50 to $200–300

- Zimbabwe hosts East Africa’s first carbon-neutral data center, powered by solar plus battery storage

This is not aspirational. Indonesia achieved comparable transformation in nickel within five years. Chile is executing a similar strategy for lithium, requiring domestic processing for exploitation permits issued after 2023.

Those who control energy storage increasingly control access to computation. Those who control computation increasingly shape economic development. Those who mine lithium without deploying batteries remain excluded from both.

Zimbabwe has leveraged its mineral wealth before — gold, platinum, tobacco, diamonds — typically as an exporter, occasionally as a processor, rarely as a value-chain integrator.

Lithium offers a different opportunity because lithium solves Zimbabwe’s own most pressing constraint: reliable electricity.

The pathway is clear: deploy batteries domestically, assemble regionally, refine strategically. The question is political will.

Zimbabwe can remain a supplier of battery inputs and a consumer of AI services. Or it can anchor storage infrastructure, support regional compute capacity, and build resilience into its own digital future.

Lithium is not just about the future of transport. It is about the future of power, computation, and economic agency.

Those who mine the materials of the AI era without deploying them will power someone else’s future.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Owns Zimbabwe’s Lithium Mines?

Most of Zimbabwe’s lithium mines are owned by Chinese mining companies, with Western investors largely absent due to concerns over political uncertainty, sanctions, and reputational risk. Chinese firms have moved swiftly and decisively, acquiring the country’s most valuable deposits and establishing a near-total monopoly over the sector.

- Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt: Operates the Arcadia Lithium Project, one of the world’s largest hard rock resources ($700M+ total investment).

- Sinomine Resource Group: Acquired the historic Bikita Mine for ~$200M.

- Chengxin Lithium: Controls the Sabi Star Project, which has faced controversy over community displacement.

- Kuvimba Mining House: A state-owned entity partnering with Chinese firms to develop the Sandawana Mine.

Why is Zimbabwe important in the global lithium market?

As global demand for lithium increases due to electric vehicles, energy storage, and AI infrastructure, Zimbabwe’s reserves position it as a strategically important supplier in the global battery value chain.

To ensure the country retains more value from its “white gold,” the government has implemented aggressive policies:

- 2022: Banned the export of raw, unprocessed lithium ore.

- 2027: Plans to ban the export of lithium concentrate to force local processing into battery-grade materials.

How much lithium does Zimbabwe produce?

Zimbabwe has rapidly increased lithium production in recent years due to new investments and expanded mining operations. Output is primarily in the form of spodumene concentrate, which is exported for further refining abroad. Precise annual production figures vary by year and project expansion.

What is lithium beneficiation?

Lithium beneficiation refers to processing raw lithium ore into higher-value products such as:

- Spodumene concentrate

- Lithium carbonate

- Lithium hydroxide

- Cathode materials

Each additional processing stage significantly increases export value and job creation potential.

Why doesn’t Zimbabwe manufacture lithium batteries yet?

Battery manufacturing requires:

- Reliable and affordable electricity

- Industrial infrastructure

- Skilled technical labor

- Large-scale capital investment

- Stable regulatory frameworks

Zimbabwe currently faces electricity shortages and infrastructure constraints that limit immediate battery cell production. Addressing power stability is a critical prerequisite.

How does lithium connect to artificial intelligence (AI)?

AI systems require massive computing infrastructure, which depends on stable electricity and grid-scale energy storage. Lithium-ion batteries are central to renewable integration and backup power systems used by data centers. As AI demand increases globally, lithium becomes more strategically important.

Who dominates the global lithium supply chain?

China currently dominates lithium refining and battery cell manufacturing capacity. While countries like the United States and members of the European Union are investing in domestic supply chains, much of the world’s lithium refining remains concentrated in Asia.

A phased industrial strategy could allow Zimbabwe to move up the value chain over time.

Other African Countries Producing Lithium

| Country | Key Projects & Status |

| Namibia | 2nd largest producer in Africa (~17% of output); partnership with the EU. |

| Mali | Goulamina Project; production began around 2024. |

| DRC | Home to the Manono deposit, potentially Africa’s largest lithium resource. |

| Ghana | Ewoyaa Project; notable for being backed by American capital (Piedmont Lithium). |

| Nigeria | Commissioned its first Chinese-developed processing plant in May 2024. |

Also, read our article on Zimbabwe’s Controversial Partnership with CloudWalk

References

BloombergNEF. (2024). Global Energy Storage Outlook.

International Energy Agency. (2024). Data Centers and Data Transmission Networks Report.

International Energy Agency. (2024). Global EV Outlook.

UNCTAD. (2024). Critical Minerals Brief: Strategic Value Chain Development.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2024). Mineral Commodity Summaries: Lithium.

World Bank. (2023). Zimbabwe Manufacturing Capacity Utilization Report.