When a Harare commuter walks through Robert Mugabe International Airport, cameras track their every move. Their face is scanned, analyzed, and matched against a growing database, not just for Zimbabwe’s security records, but potentially for training AI systems thousands of miles away in Shenzhen, China. This has been Zimbabwe’s reality since 2018, when the government partnered with CloudWalk Technology in a deal that promised enhanced security but sparked a global debate about data sovereignty, racial bias in AI, and what some scholars now call “algorithmic coloniality.”

AI Surveillance, Data Ethics, and Africa’s Tech Future

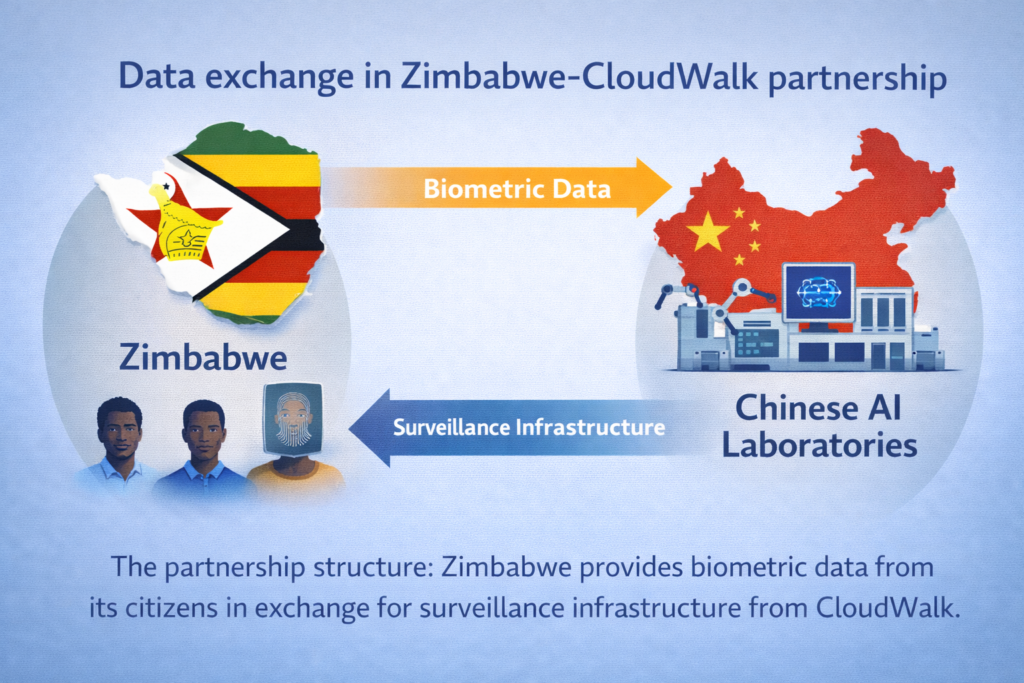

7 years later, Zimbabwe signed an agreement with the Chinese facial recognition firm CloudWalk Technology to deploy surveillance systems across airports, borders, and public spaces. In exchange for this security infrastructure, Zimbabwe would provide something uniquely valuable: millions of biometric data points from darker-skinned faces to help train AI algorithms that historically performed poorly on African populations. The deal initially drew sharp criticism from privacy advocates who warned of “data colonialism” and surveillance overreach.

Facial recognition cameras monitor travelers at Zimbabwe’s main international airport as part of the 2018 CloudWalk Technology partnership

Now, in 2025, the partnership’s legacy has grown more complex. Recent expansions in 2023 brought additional Chinese firms like Hikvision into Zimbabwe’s surveillance ecosystem, while academic discourse has evolved from simple privacy concerns to deeper critiques of digital neocolonialism. As African nations increasingly turn to Chinese technology partners for digital infrastructure, Zimbabwe’s experience offers critical lessons, both cautionary and practical, about navigating these partnerships.

This article explores the CloudWalk deal’s seven-year journey, weighing technological benefits against mounting ethical concerns, and examining what Zimbabwe’s experience means for Africa’s digital future. From improved border security to accusations of treating citizens as “guinea pigs” for AI development, the story reveals the complex trade-offs African nations face in the global race for technological advancement.

Background on Facial Recognition Bias and Global Context

To understand why Zimbabwe’s biometric data became so valuable to CloudWalk, we must first examine a fundamental problem in artificial intelligence: facial recognition systems have historically been significantly less accurate at identifying people with darker skin tones.

The AI Bias Problem: Why Darker Skin Matters

Multiple studies have documented this alarming bias:

- Research from MIT and Stanford found error rates for darker-skinned women were up to 34% higher than for lighter-skinned men

- In some cases, algorithms performed 10 to 100 times worse on African faces compared to Caucasian faces

- The problem stems from training datasets overwhelmingly composed of lighter-skinned faces from North America, Europe, and East Asia

This is a systemic failure rooted in how AI systems are trained. For African populations, this bias means higher rates of false identification, wrongful surveillance matches, and exclusion from identity verification systems spanning airport security to banking applications.

China’s Strategic AI Expansion in Africa

This technical reality created a market opportunity. As China positioned itself as a global leader in AI and surveillance technology through its Belt and Road Initiative, companies like CloudWalk recognized that achieving truly global market dominance required solving the “darker skin problem.” African nations, with their large populations and often limited regulatory oversight, became prime targets for data collection partnerships.

China’s surveillance technology exports have expanded rapidly across Africa over the past decade:

- Huawei has installed “Safe City” systems in Kenya and Uganda

- ZTE has deployed surveillance infrastructure in Ethiopia

- Hikvision cameras monitor streets in dozens of African cities

These partnerships serve multiple Chinese strategic interests: extending geopolitical influence, creating markets for Chinese technology exports, and crucially, gathering diverse datasets to improve AI algorithms.

Africa’s Infrastructure Gap and Limited Options

For African nations, these partnerships arrive at a moment of acute need. The continent is experiencing rapid urbanization and digital transformation, yet faces massive infrastructure gaps and limited access to Western capital and technology. Chinese firms offer favorable financing, quick deployment, and willingness to work in markets that Western companies often avoid due to political risk or limited profitability.

This creates a dynamic where African governments face difficult choices: accept Chinese technology partnerships with potential strings attached, or forgo modernization altogether. Zimbabwe’s decision to partner with CloudWalk emerged from this context. A nation seeking technological advancement, facing economic constraints and limited alternatives, met a Chinese company eager for the exact resource Zimbabwe could provide: millions of darker-skinned faces to train its algorithms.

The 2018 CloudWalk-Zimbabwe Deal: Details and Initial Rollout

The Terms: Infrastructure for Data

In 2018, the Zimbabwean government and CloudWalk Technology formalized a strategic partnership that would reshape the nation’s surveillance landscape. The deal’s structure was straightforward but unprecedented: CloudWalk would provide, install, and maintain facial recognition systems across Zimbabwe’s airports, border crossings, and eventually public spaces throughout major cities. In exchange, Zimbabwe would grant CloudWalk access to the biometric data collected through these systems (photographs, facial maps, and associated identity information) to improve the company’s AI algorithms.

What Zimbabwe Would Get

- Modernized security infrastructure at minimal upfront cost

- CloudWalk financing for technology deployment with favorable payment terms

- National database for identifying individuals at borders and airports

- Capability to track criminal suspects across the surveillance network

What CloudWalk Would Gain

- Access to millions of facial images from Zimbabwe’s 15 million predominantly Black African population

- Underrepresented demographic data for training datasets

- Ability to refine algorithms and reduce error rates for darker skin tones

- Competitive advantage for contracts across Africa, Middle East, Latin America, and Caribbean

Implementation and Technology Deployment

Implementation began swiftly. By 2019, CloudWalk facial recognition cameras and processing systems were operational at Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport in Harare. Border posts with neighboring South Africa, Mozambique, and Zambia received similar systems throughout 2019 and 2020, creating an integrated surveillance network.

The technology itself represented sophisticated capabilities:

- Identify individuals in crowds

- Track movement across multiple cameras

- Flag matches against databases of wanted individuals

- Function in various lighting conditions and angles

By 2020, reports indicated that millions of facial scans had been collected and processed. Estimates suggested that virtually every Zimbabwean passing through major airports or border crossings had been added to the database. For a nation with limited prior biometric identification infrastructure, this represented a dramatic leap into comprehensive digital surveillance.

The Transparency Problem

Notably absent from early implementation reports were details about data protection measures, citizen notification protocols, or oversight mechanisms. Zimbabweans moving through airports and borders were scanned automatically, typically without:

- Explicit consent

- Clear signage indicating facial recognition use

- Information about data storage and usage

- Access to their collected data or correction processes

This lack of transparency would become a central criticism as international attention to the deal intensified.

Claimed Benefits: Security, Innovation, and Economic Ties

Enhanced Security and Public Safety

Proponents of the Zimbabwe-CloudWalk partnership have emphasized several tangible and potential benefits that extend beyond simple surveillance capabilities.

For Zimbabwe, the most immediate claimed advantage has been enhanced border security and public safety:

- Faster processing times at immigration checkpoints

- Quicker identity verification compared to manual passport checks

- Identification of wanted individuals at border crossings

- Theoretical improvements in tracking criminal activity

Government officials have cited examples of wanted individuals being identified who might have otherwise entered or exited the country undetected. While independent verification of these specific cases remains limited, the theoretical security benefits of such technology are well-established in other contexts.

Financial Inclusion Potential

Financial inclusion represents another potential benefit frequently mentioned by deal supporters. Facial recognition technology can enable banking and mobile money services in populations with limited documentation. In a country where many citizens lack traditional forms of identification, biometric verification could theoretically:

- Provide access to previously unavailable financial services

- Enable opening bank accounts and accessing loans

- Facilitate transaction verification using facial recognition

However, concrete implementation of these applications has been slower to materialize than security-focused deployments.

Strategic Benefits for CloudWalk and China

For CloudWalk and China more broadly, the partnership has delivered clear strategic advantages:

- Successfully positioned as a leader in cross-demographic facial recognition accuracy

- Zimbabwe data contributed to algorithm improvements marketed globally

- Secured additional contracts across Africa and other regions

- Significant return on investment through competitive advantage from unique training data

The partnership also fits within China’s Belt and Road Initiative framework, strengthening economic and political ties. Beyond the CloudWalk deal itself, Zimbabwe has pursued additional Chinese partnerships for power generation, telecommunications, and transportation projects.

The Evidence Gap

However, these claimed benefits must be weighed against a critical caveat: much of the evidence remains anecdotal or provided by interested parties:

- Zimbabwe’s government has released limited data on specific security improvements

- CloudWalk’s algorithm improvements haven’t been independently verified

- Financial inclusion applications remain largely theoretical

- Technology transfer has been modest, with local technicians performing maintenance rather than development roles

This limited evidence base suggests that the surveillance infrastructure’s advantages may be narrower and less transformative than initially promoted, particularly when weighed against the substantial ethical and privacy risks.

Critics warn that facial recognition technology could be used to monitor political opposition and suppress dissent in Zimbabwe

Criticisms and Ethical Concerns

While proponents emphasize security and development benefits, the Zimbabwe-CloudWalk partnership has faced intense criticism from human rights organizations, privacy advocates, technology ethicists, and increasingly, African civil society groups. These criticisms have evolved and deepened over the partnership’s seven years, moving from initial privacy concerns to more fundamental questions about digital sovereignty and what scholars now term “algorithmic coloniality.”

Privacy and Surveillance Risks

Political Control and Repression

The most immediate concern centers on mass surveillance and its implications in Zimbabwe’s political context. Human rights organizations including Privacy International and Amnesty International have documented Zimbabwe’s history of political repression, including monitoring of opposition activists, journalists, and civil society leaders.

The CloudWalk facial recognition system provides the government with unprecedented capability to:

- Track citizens’ movements in real-time

- Identify individuals at protests or political gatherings

- Create comprehensive profiles of travel patterns and associations

- Monitor opposition activities systematically

Real-World Context

These aren’t theoretical risks. Zimbabwe’s ruling party has demonstrated willingness to use state resources for political control:

- The 2018 elections (same year as CloudWalk deal) saw violence against opposition supporters

- Subsequent 2023 elections were marked by political intimidation concerns

- History of restrictions on civil liberties during election periods

In this context, facial recognition technology becomes not just a security tool but a potential instrument of political control.

The Consent Problem

The surveillance extends beyond political applications. Zimbabweans moving through airports, border crossings, and increasingly public spaces are being systematically tracked without:

- Meaningful consent or notification

- Opt-out provisions

- Clear data retention limits

- Accessible processes to view collected information or correct errors

This represents a fundamental shift in the relationship between citizen and state, from presumed privacy to presumed surveillance.

“Algorithmic Coloniality” and Data Exploitation

Digital Age Resource Extraction

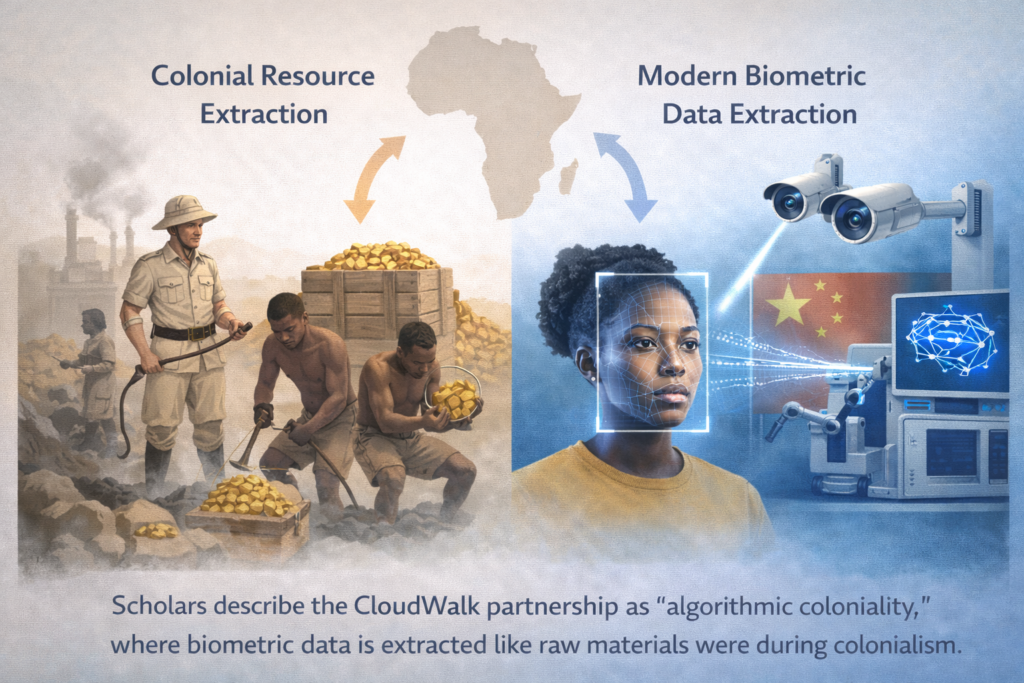

Recent academic analysis has introduced a more nuanced critique through the framework of “algorithmic coloniality.” This concept suggests that Zimbabwe’s partnership represents a new form of colonial extraction, where the resource being extracted is biometric data rather than minerals or agricultural products.

A 2024 paper in the Transcience Journal examining Chinese AI surveillance technology in Zimbabwe argues that the partnership replicates historical colonial dynamics in digital form:

- Colonial powers extracted raw materials from Africa for European processing

- CloudWalk extracts raw biometric data from Zimbabwe for Chinese AI laboratory processing

- Value created (improved algorithms, enhanced products, market advantages) accrues primarily to CloudWalk

- Zimbabwe receives only initial infrastructure

The Asymmetry of Value

This framework highlights a disturbing asymmetry:

- Zimbabweans provide irreplaceable raw material (their facial data)

- Little stake in resulting intellectual property or commercial benefits

- CloudWalk’s improved algorithms will generate revenue for years or decades

- Zimbabwe’s benefit limited to initial surveillance infrastructure

- Essentially: permanent, valuable resource traded for temporary technology access

The Racial Dimension

The racial dimension of this extraction is particularly troubling. CloudWalk specifically sought African facial data because existing algorithms performed poorly on darker skin tones, a problem created by historical exclusion of African faces from AI development.

Rather than inclusive technology development, critics argue this reflects exploitation:

- African data is valuable precisely because African people were systematically excluded

- Zimbabweans provide the solution to a problem they didn’t create

- No fair compensation for their contribution

- Historical pattern of using African populations to solve problems benefiting others

Digital Sovereignty Erosion

A 2025 analysis from the Research Society of International Studies describes this as erosion of “digital sovereignty,” referring to Zimbabwe’s ability to control and benefit from its citizens’ data:

- Once biometric data flows to Chinese servers, limited ability to control its use

- Cannot effectively track dissemination or claim ownership over AI improvements

- Loss of sovereignty over critical 21st-century resource

- Parallels historical losses of sovereignty over physical resources during colonial periods

Human Rights and Democratic Backsliding

International human rights organizations have raised alarms about the CloudWalk partnership’s contribution to democratic erosion in Zimbabwe. The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre documented in 2023 that the surveillance expansion (which by then included not just CloudWalk but additional Chinese firms like Hikvision) was being deployed with minimal oversight or legal framework.

Key Concerns

Chilling Effects on Free Expression: When citizens know they may be identified and tracked while attending political rallies, associating with opposition groups, or even moving through public spaces, self-censorship increases. The mere existence of pervasive facial recognition creates what privacy scholars call a “chilling effect.” People modify their behavior not because they’re actually being monitored in any given moment, but because they can’t know when they might be.

Lack of Legal Safeguards: Zimbabwe lacks comprehensive data protection legislation. At the time the CloudWalk deal was signed in 2018:

- No legal restrictions on biometric data collection

- No requirements for consent

- No data retention limits

- No meaningful oversight bodies

- Zimbabwe only began drafting a Data Protection Bill in 2023, five years after mass surveillance commenced

Asymmetric Power Dynamics: The facial recognition system gives authorities immense power over citizens, with no reciprocal accountability:

- Government officials can identify any Zimbabwean moving through monitored spaces

- Citizens have no visibility into who accesses their data

- No information on purposes or safeguards

- No mechanisms for challenging misuse

Enabling Authoritarianism: Perhaps most fundamentally, critics argue that partnerships like CloudWalk’s make authoritarianism more efficient and sustainable. These systems don’t create authoritarianism (Zimbabwe’s governance challenges predate CloudWalk) but they do make authoritarian control easier, cheaper, and more comprehensive. A government that previously struggled to monitor opposition movements can now do so automatically and systematically.

Data Sovereignty and the “Guinea Pig” Narrative

Unwitting Participation in AI Development

Civil society groups within Zimbabwe and across Africa have increasingly framed the CloudWalk deal using the language of exploitation, describing Zimbabweans as “guinea pigs” for Chinese AI development. This characterization reflects several intersecting concerns:

Lack of Meaningful Consent:

- Government agreed to partnership, but individual citizens were not informed

- No notification about contributing to algorithm development

- No options to opt out

- No compensation for data’s value

- Unwitting participants in massive AI training program

Asymmetric Risk Distribution:

- Risks of experimental technology borne by Zimbabweans

- If systems malfunction or produce false positives, Zimbabweans suffer consequences

- Commercial benefits of improved algorithms accrue to CloudWalk and global clients

- Benefits flow elsewhere while risks remain local

Historical Parallels

Third, there’s a troubling historical resonance. Africa has long experience with medical and scientific research conducted on African populations without adequate consent or benefit-sharing:

- Colonial-era medical experiments

- More recent pharmaceutical trials

- Pattern of African bodies used to advance external interests

The CloudWalk partnership evokes this history, substituting biometric data collection for medical experimentation, but maintaining the same fundamental dynamic of African identities being used to advance external interests without fair compensation or genuine consent.

Zimbabwe’s Official Position and Counterarguments

Core Government Defense

The Zimbabwean government has consistently defended the CloudWalk partnership, framing criticism as Western interference in Africa’s right to choose its own development partners. Officials emphasized several counterpoints:

Sovereignty and Development:

- Zimbabwe has the right to pursue technological partnerships serving development needs

- Western nations extensively deploy facial recognition (US law enforcement, UK public spaces)

- Questions double standard in singling out African-Chinese partnerships

Security Imperatives:

- Highlighted tangible security improvements

- Faster processing at border crossings

- Enhanced ability to track criminal activity

- 2023 Ministry of Home Affairs claimed technology helped identify wanted individuals (though independent verification remains limited)

Economic Pragmatism:

- Chinese firms offer favorable financing terms

- Faster deployment compared to Western alternatives

- Facing economic sanctions and limited Western capital access

- Chinese partnerships represent one of few viable paths to modernizing infrastructure

Data Protection Assurances:

- Claimed data-sharing agreements include protections

- Zimbabwe retains control over citizens’ information

- However, critics note lack of comprehensive data protection legislation makes assurances difficult to verify

The Fundamental Tension

These defenses reveal a fundamental tension: Zimbabwe’s government views the partnership through a lens of pragmatic development and technological sovereignty, while critics see it as a Faustian bargain sacrificing long-term data rights for short-term infrastructure gains.

Notably, the government has been less responsive to questions about:

- Oversight mechanisms

- Independent audits of technology deployment

- Specific details about data collection and storage

- These silences fuel ongoing skepticism among civil society groups

Updates and Recent Developments (2023–2025)

As the CloudWalk partnership enters its seventh year, recent developments reveal both continuity and evolution in Zimbabwe’s approach to surveillance technology and Chinese partnerships.

2023: Expansion and Integration

Hikvision Enters the Picture

The most significant development in 2023 was Zimbabwe’s decision to expand its surveillance infrastructure beyond CloudWalk to include additional Chinese firms. Hikvision, one of the world’s largest surveillance equipment manufacturers, secured contracts to deploy cameras and facial recognition systems in:

- Harare’s central business district

- Other urban centers across Zimbabwe

- Shift from controlled access points (airports, borders) to ambient surveillance in public spaces

This expansion received:

- Little public consultation

- Even less transparency about safeguards or limitations

- No new legal frameworks to govern expanded surveillance

Civil Society Response

The expansion drew immediate criticism:

- Business & Human Rights Resource Centre documented minimal public consultation

- No new legal frameworks to govern technology use

- African Defense Forum reported comprehensive monitoring network created concerns about citizen tracking scope

- Integration of multiple Chinese systems raised coordination concerns

Academic Critical Mass: The emergence of “algorithmic coloniality” as an analytical framework reflects deepening scholarly consensus that these partnerships represent problematic power dynamics requiring more than superficial reform. A 2025 paper on Chinese surveillance technologies in Africa argues these systems systematically erode digital freedoms while entrenching technological dependence.

Global Regulatory Divergence: The European Union’s AI Act, implemented in 2024, establishes strict regulations on biometric surveillance and high-risk AI systems. This creates a stark contrast:

- EU moves toward rights-protective AI governance

- Zimbabwe continues expanding minimally regulated surveillance

- Growing divergence highlights how African nations risk being left behind in global AI ethics norm-setting

Broader Chinese Technology Dependency

Simultaneously, Zimbabwe’s relationship with Chinese technology firms deepened beyond surveillance:

- Telecommunications infrastructure contracts

- Power generation projects

- Smart city initiatives

- Increasing dependency across multiple critical sectors

- Complicates future efforts to reassess or limit surveillance partnerships

2024: Sustained Deployment and Academic Scrutiny

System Operations

Throughout 2024, CloudWalk and Hikvision systems continued operating and expanding, though at slower pace than initial rollout:

- Government reports suggested millions of facial scans processed monthly

- National biometric database encompasses substantial portion of population

- Focus on maintaining and optimizing existing infrastructure

Academic Critical Analysis

Intensified academic scrutiny marked 2024:

- Multiple peer-reviewed papers analyzed partnership through critical lenses

- Transcience Journal’s detailed “algorithmic coloniality” examination

- Framework influenced subsequent scholarly and civil society discourse

- Shifted conversation from privacy violations to digital sovereignty, post-colonial power dynamics, and technological dependency

Global AI Governance Evolution

The global AI governance landscape evolved significantly:

- European Union’s AI Act came into force

- Strict regulations for high-risk AI applications including biometric surveillance

- Several African nations (Nigeria, Kenya) accelerated AI governance initiatives

- Zimbabwe’s minimal regulatory approach appeared increasingly anomalous

- Questions raised about future participation in global data flows and digital trade

2025: Stagnation, Diversification, and Broader Context

Partnership Plateau

As of 2025, the CloudWalk partnership appears to have reached a plateau:

- No major new surveillance deployments announced

- Limited evidence of significant technological upgrades

- Focus on maintaining existing systems

- Expanded capabilities beyond current infrastructure limited

Factors Explaining Stagnation

- Zimbabwe’s intensified economic challenges limiting government resources

- International criticism creating reputational costs

- Basic surveillance infrastructure largely in place

- Diminishing returns for government’s stated security objectives

Technology Partnership Diversification

Interestingly, Zimbabwe has begun diversifying technology partnerships in other sectors:

- Engagement with Starlink for internet connectivity

- May reflect recognition that over-dependence on Chinese technology creates vulnerabilities

- Different sectors require different technological solutions

- Technology strategy becoming more complex than simple Chinese alignment

Tentative AI Governance Steps

Zimbabwe’s government made preliminary moves toward broader AI governance:

- Late 2024 and early 2025 discussions on national AI strategy

- Mentions of ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks

- Discussions remain preliminary with no concrete legislation

- No enforcement mechanisms yet established

- Critics note irony of developing AI ethics policies years after deploying mass surveillance

Global Context and Comparative Developments

Regional Digital Governance Trends

Zimbabwe’s experience must be understood against broader 2024-2025 trends in African digital governance:

- Nigeria passed comprehensive data protection legislation with meaningful enforcement mechanisms

- Kenya launched investigations into foreign technology partnerships demanding transparency

- South Africa continued developing its AI ethics framework

- These developments highlight Zimbabwe’s outlier status

While peer nations strengthen oversight and citizen protections, Zimbabwe maintains minimal regulation of its most intrusive surveillance technologies.

Maturation of Global AI Ethics Conversation

The global conversation about AI ethics and surveillance has matured significantly:

- Began as niche concerns among privacy advocates

- Now mainstream policy debate

- Major democracies implementing restrictions on facial recognition and biometric surveillance

- Creates both pressure and opportunity for African nations

This evolution means:

- Pressure to conform to emerging international norms

- Opportunity to shape norms by asserting African perspectives and interests

Zimbabwe’s Mixed Legacy in 2025

For Zimbabwe specifically, the CloudWalk partnership’s legacy is mixed:

- Surveillance infrastructure persists and functions

- Government has monitoring capabilities it lacked a decade ago

- Generated lasting reputational damage

- Positioned as cautionary tale in tech partnership discussions

- Left with dependence on foreign technology it cannot independently maintain or modify

The fundamental questions remain unresolved: How should African nations balance security needs with privacy rights? What constitutes fair value exchange in data-for-infrastructure partnerships? How can nations assert digital sovereignty while participating in global technology ecosystems?

Comparative Analysis: Zimbabwe in Africa’s Broader Surveillance Landscape

Zimbabwe’s CloudWalk partnership doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s part of a continental pattern of African nations adopting Chinese surveillance technology, each with distinct outcomes that offer valuable lessons.

Nigeria: Regulatory Evolution After Deployment

Nigeria initially embraced Chinese surveillance technology through a $1.5 billion contract with Huawei in 2019 to install thousands of CCTV cameras across Lagos and Abuja under the “Safe City” initiative.

Key Development: Nigeria has shown greater regulatory evolution than Zimbabwe:

- 2023: Passed comprehensive Data Protection Act with significant enforcement mechanisms

- Includes regulatory commission with power to audit foreign tech partners

- Legal framework established after Chinese partnerships began

- Demonstrates how nations can retroactively assert data sovereignty

- Nigerian civil society groups successfully used laws to demand transparency about data flows

Lesson: Legal infrastructure can partially mitigate risks even in existing partnerships

Kenya: The Technology Transfer Gap

Kenya deployed Huawei’s facial recognition technology in 2019 for its Standard Gauge Railway and urban surveillance systems.

Mixed Results:

- Technology reportedly improved security screening efficiency by 40%

- 2022 investigation revealed Chinese engineers retained administrative access for years

- Minimal Kenyan oversight of foreign-controlled systems

Lesson: Importance of technology transfer provisions and local capacity building, areas where Zimbabwe’s deal appears notably weak

Ethiopia: Comprehensive Integration, Concentrated Risk

Ethiopia’s partnership with Chinese firms extends beyond surveillance to encompass a comprehensive digital ID system (Fayda) that integrates facial recognition with national identification.

Context:

- Launched in 2020 with Chinese technical support

- Aims to formalize Ethiopia’s largely undocumented population

- More holistic approach than Zimbabwe’s security-focused deployment

- Concentrates vast sensitive data with limited regulatory oversight

2024 Warning Sign: System outages paralyzed banking and government services, highlighting infrastructure dependency risks

Uganda: Worst-Case Scenario Realized

Uganda has perhaps gone furthest in deploying Chinese surveillance, installing Huawei facial recognition cameras throughout Kampala in 2019.

Documented Political Misuse:

- Tracked political opposition members during contentious 2021 elections

- Explicit political application far beyond stated security purposes

- Represents Zimbabwe critics’ worst-case scenario made real

Lesson: Validates concerns that surveillance infrastructure, once established, inevitably expands to serve political control, particularly with weak democratic checks

South Africa: The Road Not Taken

South Africa considered but ultimately rejected a similar CloudWalk proposal in 2019.

Rejection Factors:

- Cited inadequate data protection safeguards

- Concerns about Chinese government access to citizen data

- Made possible by stronger democratic institutions

- More developed local tech capacity

Lesson: African nations with robust governance structures can resist problematic deals, though option may be less available to countries facing Zimbabwe’s economic constraints

Key Lessons for African Digital Sovereignty

These comparative cases reveal several critical patterns:

- Legal Frameworks Matter: Nigeria’s post-facto data protection law shows regulatory infrastructure can be built even after partnerships commence, though proactive legislation (as South Africa attempted) is preferable.

- Technology Transfer is Essential: Kenya’s experience demonstrates that without genuine technology transfer and local capacity building, African nations remain perpetually dependent on foreign technicians who may retain control over systems.

- Scope Creep is Predictable: Uganda’s political use of surveillance technology validates the “slippery slope” argument. Security infrastructure deployed for legitimate purposes can easily expand to serve authoritarian ends, particularly in contexts with weak democratic checks.

- Economic Constraints Shape Options: South Africa’s ability to reject the CloudWalk deal reflects its relatively stronger economy and existing tech sector. For nations like Zimbabwe facing severe economic challenges, the calculus differs significantly. This reality is often overlooked in Western critiques.

- Regional Cooperation Could Strengthen Bargaining: No comparative case shows significant regional coordination, yet collective negotiation by African Union members could potentially secure better terms, stronger safeguards, and more favorable technology transfer provisions than individual nations achieve alone.

Recommendations for Future African Tech Partnerships

Drawing from Zimbabwe’s experience and regional comparisons, African nations should consider these ten critical recommendations:

1. Establish Data Protection Laws First

- Prioritize comprehensive data protection legislation before signing major surveillance or biometric technology deals

- Include provisions for consent, data retention limits, and citizen access rights

- Create independent oversight bodies with enforcement authority

- Don’t wait until after deployment

2. Demand Technology Transfer Provisions

- Require contracts to include specific timelines for transferring technical knowledge and administrative control to local personnel

- Specify that within defined timeframes (e.g., 3-5 years), local technicians will have full administrative access

- Build local capacity, not perpetuate dependency

- Ensure independent operational capability

3. Build Independent Oversight

- Create independent regulatory bodies with technical expertise and legal authority

- Model on Nigeria’s Data Protection Commission

- Grant power to inspect systems, review data flows, investigate complaints

- Impose penalties for violations

4. Diversify Technology Partners

- Engage multiple international partners (Chinese, European, American, other African nations)

- Avoid over-dependence on any single foreign power

- Follow Rwanda’s approach of working simultaneously with multiple tech partners

- Provides leverage in negotiations and reduces vulnerability

5. Prioritize Local Innovation

- Invest in domestic AI research and tech education

- Build homegrown alternatives to foreign technology

- Learn from Ghana’s AI lab investment and Nigeria’s growing tech startup ecosystem

- Long-term digital sovereignty requires indigenous capabilities

6. Regional AI Ethics Framework

- Support African Union efforts to develop continent-wide AI ethics guidelines

- Create data governance standards that strengthen individual nations’ bargaining positions

- Unified African approach provides greater leverage with technology providers

- Establish African perspectives in global AI governance

7. Public Transparency

- Ensure technology partnership contracts are publicly available

- Allow appropriate redactions for legitimate security concerns

- Enable civil society oversight and democratic accountability

- Require regular public reporting on system performance and data protection measures

8. Fair Value Assessment

- Conduct independent assessments of data value before entering data-for-infrastructure deals

- Recognize biometric data as finite resource

- Once collected and exported, nations lose control over its use

- Structure partnerships with ongoing revenue sharing, equity stakes in intellectual property, or guaranteed access to improved technologies

9. Sunset Clauses and Review Mechanisms

- Include provisions for regular review of partnerships

- Establish specific criteria for continuation, modification, or termination

- Enable adaptation as technology evolves rapidly

- Avoid locking nations into outdated arrangements

10. Civil Society Engagement

- Involve civil society organizations, academic institutions, and citizens in technology governance decisions

- Conduct public consultation before major surveillance deployments

- Ensure ongoing civil society representation in oversight bodies

- Create accessible complaint mechanisms for citizens

- Technology should serve public interest, not only government objectives

The Path Forward

Zimbabwe’s CloudWalk partnership, viewed alongside these regional experiences, ultimately highlights a fundamental challenge: African nations need technological infrastructure to develop and compete globally, yet many lack the economic leverage, technical capacity, and regulatory frameworks to negotiate partnerships that fully protect citizen rights and national sovereignty.

The answer isn’t to reject Chinese (or any foreign) technology partnerships entirely, but to approach them with:

- Stronger safeguards

- Greater transparency

- Realistic assessment of both benefits and risks

- Clear understanding of true costs

Success Factors: The partnerships that will succeed are those that:

- Genuinely build local capacity

- Respect citizen rights

- Create frameworks for shared benefit rather than one-sided extraction

- Include meaningful oversight and accountability mechanisms

Zimbabwe’s experience demonstrates what happens when these principles are absent: a cautionary tale that future partnerships would be wise to heed.

Conclusion

Seven years after Zimbabwe partnered with CloudWalk Technology, the deal’s legacy remains deeply ambiguous. It is neither the unqualified security success that proponents promised, nor the complete disaster that critics feared, but something more complex and troubling. Zimbabwe gained surveillance infrastructure.