At 3AM in Nairobi, Sarah Mwangi sits at her laptop, cursor hovering over the “Update Now” button. Her graphic design software needs a 2GB update to fix a critical bug. She calculates quickly: that’s two days of her weekly data bundle. The client presentation is due tomorrow, but the rent is due next week.

She closes the laptop and hopes the bug won’t crash her files.

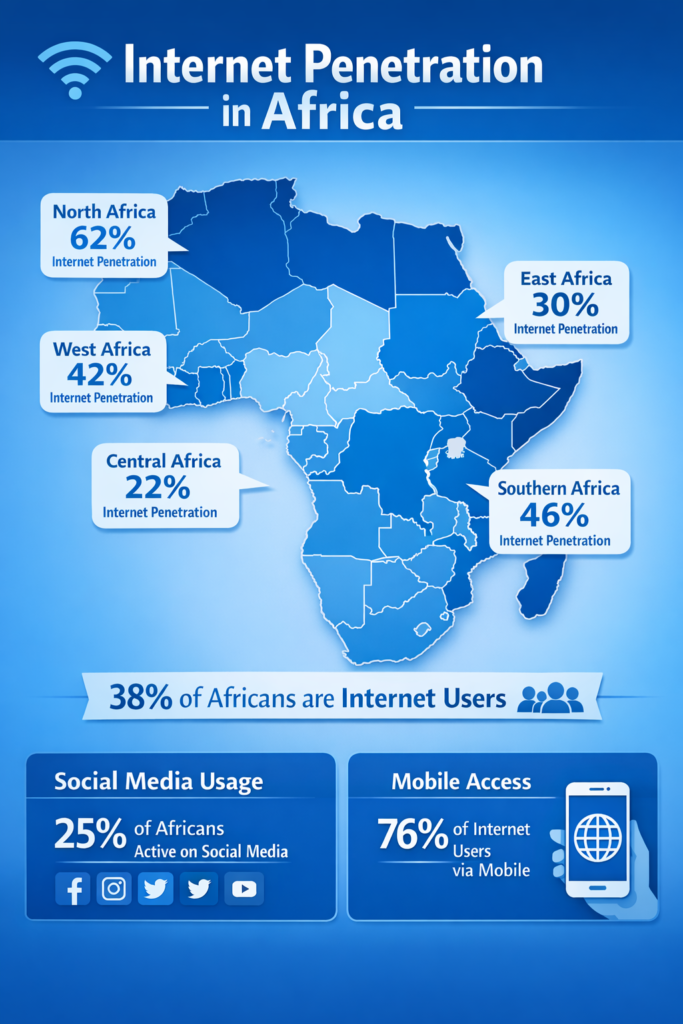

This moment — repeated millions of times across Africa — captures a paradox that defines the continent’s digital present. Africa is more connected today than at any point in its history. Smartphones are everywhere. Mobile money is mainstream. Undersea fiber-optic cables ring the continent. Governments speak fluently about digital transformation, innovation hubs, and tech-driven growth.

Yet for millions of Africans, mobile data remains painfully expensive.

Measured as a percentage of income, mobile data costs in Sub-Saharan Africa remain among the highest in the world. A basic monthly data bundle that feels insignificant in Europe or North America can represents a serious financial decision in Nairobi, Lagos, Accra, or Harare. For students, creators, small businesses, and families, internet access is still rationed, monitored, and frequently switched off when bundles run out.

In 2025, affordability, remains the core problem. World Bank-linked reporting places the average cost of 1GB of mobile data in Sub-Saharan Africa at roughly 2.4% of monthly income, above the commonly cited 2% affordability benchmark. For the poorest households, the burden is far higher, making “being online” a recurring financial trade-off rather than a default utility.

This raises a central question: why is data still expensive in Africa despite expanding network coverage and global connectivity?

High data costs stem from a layered combination of infrastructure realities, market structures, government policy, income disparities, and global dependence. Understanding these layers is essential if Africa’s digital future is to move beyond access toward true inclusion.

A Kenyan woman using a laptop to work at night, as high mobile data prices limit internet access for online jobs.

What “Expensive” Really Means: The Affordability Gap

When people say data is expensive in Africa, they don’t always mean the sticker price alone. The real issue is affordability, not just cost.

In high-income regions, mobile data prices are absorbed into relatively stable wages. In much of Africa, incomes are lower, currencies are weaker, and data is priced against global infrastructure and equipment costs. The result is a mismatch: data priced in near-global terms, paid for with local wages.

This is why small bundles dominate African markets. Users buy daily, weekly, or low-cap monthly packages, carefully rationing usage. Video calls are avoided. Cloud backups are disabled. Software updates wait for Wi-Fi that may never come. Education, creativity, and business growth are shaped not by ambition, but by data limits.

Global fibre optic connections to Africa

The Infrastructure Reality

Africa is no longer isolated from global bandwidth. Dozens of submarine cables now land on its shores, connecting the continent to Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

But, Submarine Cables Don’t Mean Cheap Inland Internet

Once international capacity arrives, it still must be transported across countries through terrestrial fiber networks — essentially, the physical cables that run along roads, under cities, and between regions. In many African states, these networks remain incomplete, unevenly distributed, or controlled by a small number of operators. Where fiber does not reach, providers rely on microwave links (wireless transmission towers), which are slower, less reliable, and more expensive per unit of data.

This is the often-ignored last-mile problem. The closer users are to dense urban fiber hubs, the cheaper data can become. The farther away they live, the higher the cost to serve them.

Beyond Cables: Power, Roads, and Daily Operations

Telecom infrastructure depends on more than cables and towers. It depends on electricity, transport, security, and maintenance access.

In regions with unreliable power grids, operators run base stations on diesel generators. Fuel costs fluctuate. Equipment must be guarded against theft. Poor road networks increase repair times and operational costs. All of this is ultimately passed on to consumers.

In short, data is expensive partly because connectivity itself is expensive to sustain in many African contexts.

Market Structure and Competition Gaps

In theory, competition should drive prices down. In practice, many African telecom markets are dominated by two or three large operators with significant pricing power.

When Few Players Control Access

Major players such as MTN, Vodacom, and Airtel Africahave built extensive networks across the continent. Their scale brings coverage and reliability — but also market concentration, meaning a small number of companies control most of the market.

In markets with limited competition, price wars are rare. Instead, operators compete on branding, bundle structure, or value-added services while keeping core data prices relatively stable. Why drop prices when your two competitors aren’t either?

The Control Problem: Vertical Integration

In some countries, the same entities control multiple layers of the internet ecosystem: international gateways, national fiber backbones, mobile networks, and retail data packages. This is called vertical integration — when one company owns multiple stages of production and distribution.

This structure makes it difficult for smaller internet service providers to enter the market or negotiate fair wholesale prices. Without strong regulatory enforcement of open-access rules (regulations requiring infrastructure owners to share networks at fair prices), dominant players can quietly preserve high margins.

More infrastructure doesn’t automatically mean lower prices.

When the same companies that own the cables also sell the data packages, and when regulators lack the power or will to enforce competitive access, new submarine cables simply increase the profits of incumbents rather than benefiting consumers.

This is why some countries see major connectivity upgrades — new cables, expanded fiber networks — yet retail data prices barely move. The pipes get bigger, but the gatekeepers remain the same.

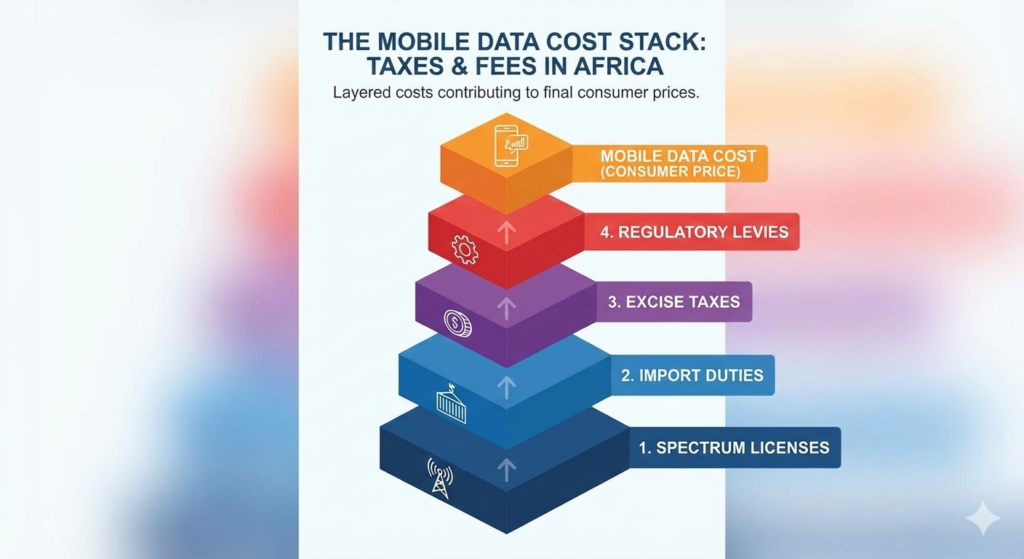

Mobile data taxes in Africa: Spectrum licenses, excise taxes, import duties, and regulatory levies

Taxes, Government Policy, and Income

When Data Is Taxed Like Luxury, Not Infrastructure

Telecom operators in many African countries face a cascade of fees and taxes:

- Spectrum licensing fees (charges for using radio frequencies)

- Annual regulatory levies

- Excise taxes on airtime and data (often 5-20% on top of regular taxes)

- Import duties on network equipment

- Universal service fund contributions (fees meant to expand rural access)

Governments often treat telecoms as reliable revenue sources, viewing them as cash-rich companies that can bear heavy taxation. The result is a layered cost stack that quietly inflates consumer prices.

When data is taxed like luxury consumption rather than treated as economic infrastructure — like roads or electricity — affordability suffers. As one Kenyan telecom analyst put it: “You can’t build a digital economy while taxing internet access like it’s alcohol.”

Policy Instability Raises Prices

Frequent policy changes, unclear spectrum rules, and unpredictable taxation increase risk for operators. Companies respond by building these uncertainties into their pricing models, essentially charging customers an “instability premium.”

Inconsistent regulation across neighboring countries also prevents regional economies of scale. Cross-border fiber links, shared infrastructure, and roaming agreements remain more expensive than they need to be because every country operates different rules.

The Global-Local Price Mismatch

Much of Africa’s telecom equipment is imported. Bandwidth contracts are often denominated in dollars or euros. When local currencies weaken, operating costs rise overnight — but local incomes don’t.

In countries facing inflation or currency instability, this effect is magnified. Even when nominal data prices stay flat, real affordability declines as wages lose purchasing power.

For low-income households, mobile data can consume a disproportionate share of monthly income. In extreme cases, the combined cost of a smartphone and basic data access rivals essential living expenses like food and transport.

The Vicious Cycle: Low Usage Keeps Prices High

A less intuitive problem is that low affordability reduces usage, and low usage keeps prices high.

When fewer people can afford meaningful data consumption:

- Networks fail to reach optimal scale economies

- Fixed costs are spread across fewer paying users

- Providers struggle to lower prices sustainably without losing money

This creates a vicious cycle where high prices limit adoption, and limited adoption reinforces high prices. Breaking this cycle requires external intervention — either regulatory pressure, new competition, or subsidized access programs.

Submarine internet cable landing buoy on an African shoreline, illustrating the infrastructure behind mobile data costs

Foreign Dependence and Digital Sovereignty

Africa remains heavily dependent on foreign suppliers for network equipment, core software systems, and international bandwidth. Companies like Huawei, Ericsson, and Nokia dominate infrastructure supply across the continent.

Imported Infrastructure, Long-Term Lock-In

Long-term contracts and proprietary systems can lock operators into costly dependencies. These partnerships enable rapid rollout, but they also shape pricing structures for years — sometimes decades. When maintenance, upgrades, and expansion all require the same foreign vendor, negotiating leverage disappears.

This raises a deeper question about digital sovereignty: who ultimately controls Africa’s digital infrastructure, and in whose interest does it operate? When the pipes are foreign-owned, when the equipment comes from abroad, and when even local content must be routed through international servers, can data ever truly be “local” and affordable?

The Data Center Gap

Local data hosting is improving, but gaps remain. In many countries, accessing “local” content — a Nigerian news site, a Kenyan university portal — still requires international routing through servers in Europe or North America, adding transit costs and latency.

Until more content, services, and cloud infrastructure are hosted locally through Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) — facilities where networks connect to exchange local traffic — African users will continue paying for unnecessary international traffic. Some countries, like Kenya and South Africa, have made progress here. Others remain years behind.

Mobile Data Affordability Across 10 Key African Markets (2025)

Mobile data prices vary sharply across Africa, shaped by market design, regulation, infrastructure maturity, and currency stability. What matters most isn’t the dollar price alone, but what that price means for local incomes.

Kenya — ~$0.40–$0.60/GB (~1.8% of average monthly income)

Strong infrastructure and early fiber investment help, but market concentration and rural coverage gaps limit further price drops. For urban middle-class users, data is manageable; for rural households, it remains a significant burden.

Nigeria — ~$0.38–$0.39/GB (~2.1% of average monthly income)

A large user base keeps prices low in dollar terms, but currency depreciation and power costs reduce real affordability. What looks cheap to outsiders feels expensive to Nigerians earning in naira.

Ghana — ~$0.08–$0.40/GB (~0.6–3.0% of average monthly income)

Strong competition and regulatory pressure make Ghana one of Africa’s more affordable markets. The National Communications Authority has actively pushed for price reductions, and it shows.

South Africa — ~$0.10–$0.20/GB (~0.4–0.8% of average monthly income)

Dense infrastructure and regulatory intervention (including high-profile data pricing investigations) lowered prices significantly. However, income inequality means affordability varies dramatically across communities.

Rwanda — ~$0.50–$0.80/GB (~3.5–5.6% of average monthly income)

State-led infrastructure investment expanded coverage impressively, but limited competition constrains retail price reductions. Rwanda is highly connected but data remains expensive relative to incomes.

Egypt — ~$1.00–$1.20/GB (~1.5–1.8% of average monthly income)

Strong backbone infrastructure and high population density help, but dominant state influence limits aggressive price competition. Affordable in absolute terms; moderate by income ratio.

Ethiopia — ~$1.50–$2.00/GB (~8.0–10.0% of average monthly income)

Market liberalization is underway with new competitors entering, but the legacy of monopoly pricing still weighs heavily on affordability. For many Ethiopians, data remains prohibitively expensive.

Zimbabwe — ~$40+/GB (100%+ of average monthly income)

Hyperinflation and currency collapse make Zimbabwe’s data among the most expensive globally. Prices fluctuate wildly; this figure reflects the acute crisis of economic instability, not just telecom policy.

Zambia — ~$7.00–$8.00/GB (~35–40% of average monthly income)

Sparse population distribution increases per-user infrastructure costs, while exchange-rate pressure drives dollar-based pricing up. One of Africa’s least affordable markets.

Morocco — ~$0.80–$1.00/GB (~1.2–1.5% of average monthly income)

Competitive market structure, strong backbone infrastructure, and North African proximity to European networks make Morocco more affordable than much of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Key insight: Low prices do not always mean affordable data. A $0.40/GB price might be manageable in South Africa but crushing in Ethiopia. Income levels, currency stability, and market design matter just as much as the sticker price.

Alternative Technologies: Promise and Limitations

New technologies are entering Africa’s connectivity landscape, raising questions about whether they’ll disrupt traditional pricing structures.

Satellite Internet (Starlink, OneWeb) Satellite providers introduce competition, especially in underserved rural areas where terrestrial networks are weak. In some markets, they outperform local networks on speed and reliability. However, high upfront hardware costs ($300–600 for equipment), regulatory approval delays, and pricing structures ($30–100+ monthly) mean satellite internet serves niche markets — businesses, remote workers, expats — rather than addressing mass-market mobile data affordability.

5G Networks Where deployed, 5G offers faster speeds and better efficiency, potentially lowering the cost per gigabyte. But 5G requires expensive spectrum licenses and significant infrastructure investment. In practice, 5G currently serves premium urban markets, not the affordability crisis in lower-income segments.

Community Networks and Wi-Fi Initiatives Some countries are experimenting with community-owned networks and public Wi-Fi programs. These can expand access in specific localities but struggle with sustainability, technical capacity, and scaling challenges.

The pattern is clear: new technologies help, but they are not silver bullets. Without addressing the underlying market structure, regulatory, and policy issues, alternatives tend to serve niche markets rather than solving systemic affordability problems.

What Has Actually Worked

Where data prices have declined meaningfully, certain patterns appear consistently:

Ghana’s Regulatory Push Ghana’s National Communications Authority took an activist approach, publicly calling out high prices and facilitating infrastructure sharing agreements. The result: Ghana moved from one of Africa’s most expensive markets to among its most affordable within a few years.

South Africa’s Competition Commission Investigation A high-profile 2019 investigation into data pricing led major operators Vodacom and MTN to reduce prices by 30-50% over subsequent years. The inquiry highlighted excessive margins and lack of competition, creating political pressure that regulatory warnings alone had not achieved.

Rwanda’s Infrastructure Model (With Caveats) Rwanda invested heavily in national fiber backbone infrastructure, dramatically expanding coverage. However, limited retail competition means prices remain high relative to income, illustrating that infrastructure alone is insufficient without competitive market structures.

Kenya’s Internet Exchange Point (IXP) The Kenya Internet Exchange Point reduced the cost of local traffic by allowing networks to exchange data locally rather than routing through expensive international links. Local content became cheaper to access, and overall efficiency improved.

Common Success Factors:

- Strong, independent, activist regulators willing to challenge incumbents

- Open-access national fiber networks (infrastructure that must be shared)

- Active Internet Exchange Points to reduce international transit costs

- Reduced sector-specific taxation (treating data as infrastructure, not luxury)

- Clear, enforced competition rules

These changes take time and political will, but they demonstrate that high data costs are not inevitable — they are policy choices.

A Nigerian student checking the remaining data balance on phone.

What Users Actually Experience: The Hidden Tax on Ambition

For ordinary users, all of this complexity translates into daily constraints:

Students attend online classes until their bundles run out mid-lecture, then drop off and miss critical content.

Entrepreneurs avoid cloud-based business tools, relying instead on WhatsApp and offline spreadsheets, limiting their ability to scale.

Creators compress videos until quality degrades, or simply abandon content creation altogether when upload costs exceed potential earnings.

Families ration video calls with relatives abroad, making digital connection feel like a luxury rather than a basic communication tool.

Small bundles run out quickly. Fear of accidental data consumption shapes behavior. Heavy reliance on zero-rated platforms (apps like Facebook that don’t count against data limits) concentrates power with big tech companies while limiting the open internet.

Digital creativity becomes shaped by cost, not talent. Expensive data quietly determines who gets to participate in the digital economy — and who watches from the margins.

Will Data Get Cheaper in Africa?

Yes — but slowly, unevenly, and not automatically.

Coverage will continue expanding. Devices will become cheaper. Infrastructure will improve. Competition from satellite providers may push incumbents in some markets. Regional cooperation may eventually reduce cross-border costs.

But without deliberate policy choices and structural reform, affordability gains will lag behind technological progress. The default trajectory is more access at persistently high relative costs, benefiting urban elites and middle classes while leaving lower-income users behind.

The real question is not whether Africa will be connected, but who gets to fully participate once it is.

Ambition Rationed by the Gigabyte

At its core, expensive data is not just a telecom issue. It is an education issue — limiting students’ access to learning resources. A productivity issue — preventing small businesses from using modern tools. A creativity issue — silencing voices that can’t afford to upload. A sovereignty issue — keeping Africa dependent on foreign infrastructure and global pricing structures.

When access to the internet is rationed, ambition is rationed too.

Africa’s digital future depends not only on cables, towers, and satellites, but on decisions about market competition, regulatory courage, taxation policy, and who the digital economy is designed to serve. Those decisions are being made now — in finance ministries setting tax rates, regulatory offices approving mergers, and parliaments debating spectrum allocation.

Until those decisions change, data may remain technically available but economically out of reach for many. And every night, someone like Sarah will sit at their laptop at 3AM, doing the math, and choosing between the software update and next week’s rent.

The infrastructure is there. The question is who it serves.