Lessons for Resource-Constrained Nations

While Washington urged countries to exclude Chinese vendors from 5G networks, Pretoria faced a harder choice: balance security risks against economic reality, or risk being left behind in the digital economy altogether.

The Global Backdrop: When 5G Became Geopolitical

In 2019, the United States launched its Clean Network Initiative, pressing partners to bar Chinese telecom giants Huawei and ZTE from 5G networks. Across Europe and Asia, governments divided: some banned Huawei outright; others restricted it to non-core functions; many simply continued as before.

In Africa, where Chinese firms have built nearly 70 percent of existing 4G networks, outright bans were never realistic. The continent’s telecom economy runs on Chinese equipment, vendor credit, and training pipelines. Removing this infrastructure would require capital that most African governments simply don’t have.

South Africa’s response wasn’t born from strategic genius—it emerged from necessity. But necessity, managed transparently and with legal guardrails, can still offer lessons worth studying.

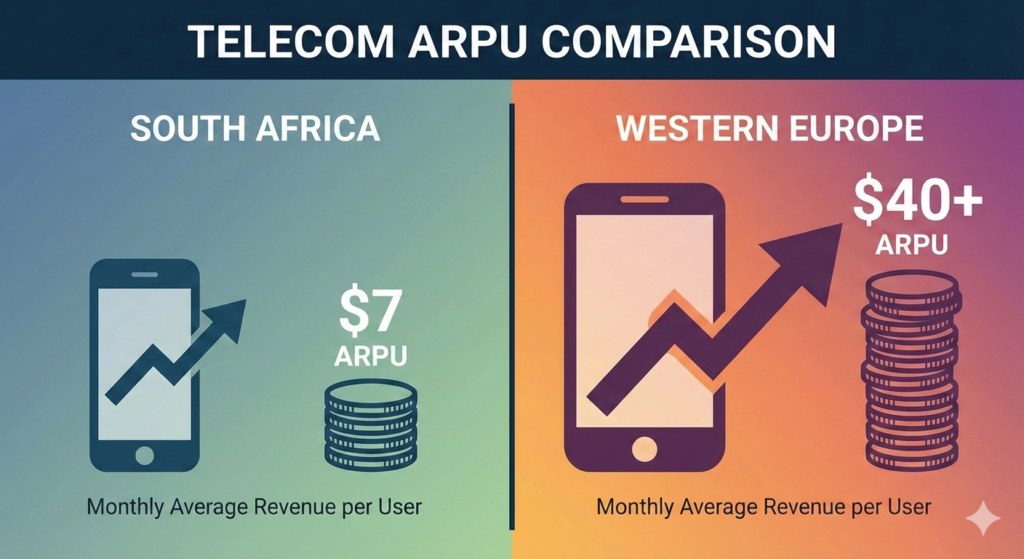

At $7 monthly average revenue per user, South African operators face fundamentally different economics than European carriers earning $40+ per subscriber

Economic Reality First: Why Bans Were Never an Option

South Africa didn’t choose to keep Huawei out of some enlightened commitment to non-alignment. The country kept Huawei because the alternative was economically catastrophic.

By 2025, Huawei and ZTE equipment formed the backbone of Africa’s digital infrastructure—including South Africa’s 4G networks and fiber backbone. MTN South Africa and Vodacom had already invested billions in Chinese equipment. Replacing it would mean:

- Capital expenditure increases of 30–40 percent if switching to Ericsson or Nokia

- 3–5 year delays in 5G rollout while infrastructure was rebuilt

- Higher consumer data prices in a market where affordability determines access

- Stranded assets worth billions in depreciated but functional equipment

“We’re not rich enough to throw away working infrastructure for geopolitical symbolism,” a senior telecom executive told Africa Tech Festival 2024, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Telecom operators face razor-thin margins in emerging markets. Vodacom’s average revenue per user (ARPU) in South Africa is roughly $7 per month—compared to $40+ in Western Europe. In this context, a 30% capex increase doesn’t just slow deployment; it makes business cases collapse entirely.

The honest assessment: South Africa’s approach is less about “charting its own course” and more about making the best of limited options. But that doesn’t make it worthless—it makes it relevant to the dozens of other countries facing identical constraints.

What South Africa Actually Did: Risk Management Within Constraints

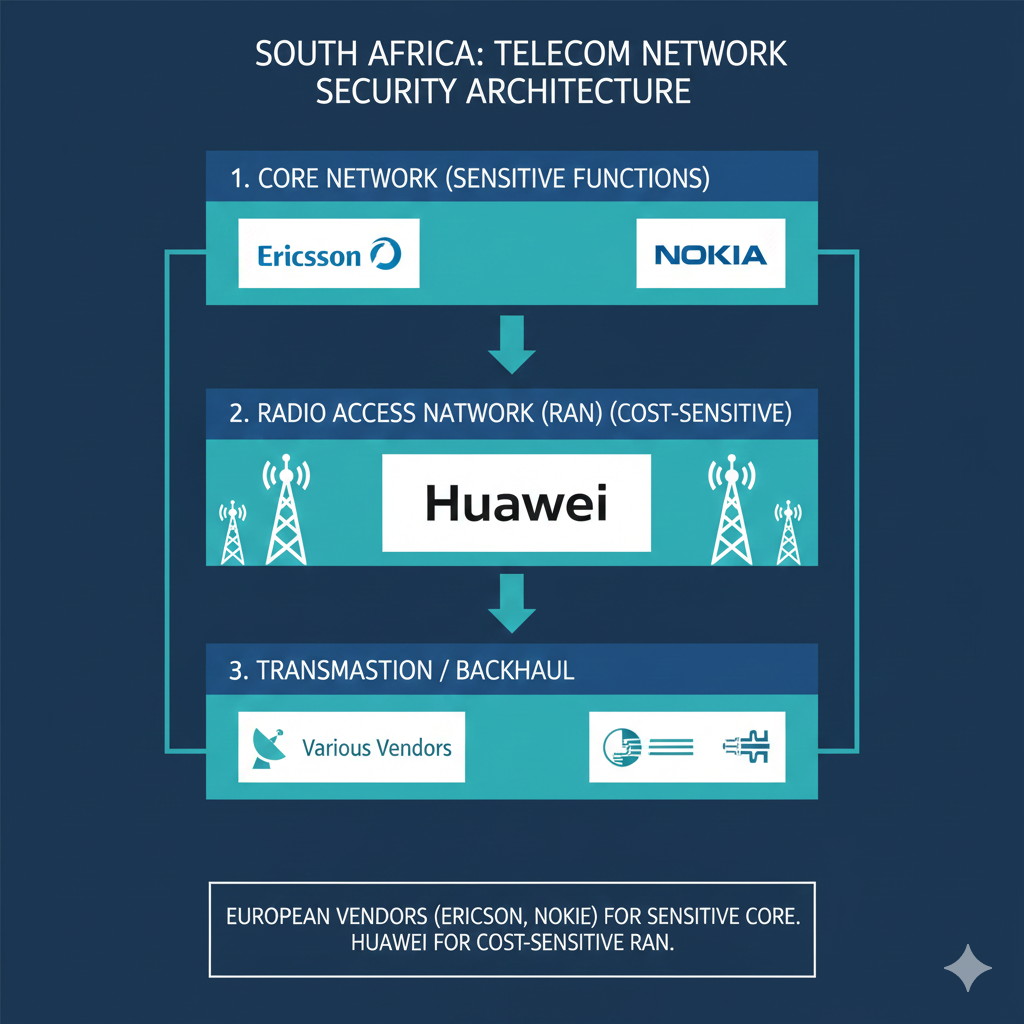

Unable to ban Chinese vendors, South Africa adopted a tiered approach based on network architecture:

Core Network (High Risk): The core—where user data is processed, calls are routed, and billing happens—is restricted to “trusted vendors.” In practice, this means Ericsson and Nokia equipment, with security audits required for deployment.

Radio Access Network (Lower Risk): The RAN—base stations and antennas that connect phones to the network—remains dominated by Huawei. This is where cost pressures bite hardest, and where Huawei’s pricing advantage (and vendor financing) is most significant.

Transmission and Backhaul: Mixed vendor environment, depending on contract negotiations and geography.

This mirrors Germany’s approach, which allows Huawei in RAN but restricts it in core functions. It’s not a perfect security architecture—vulnerabilities can exist anywhere in the network—but it reflects a calculated trade-off: protect the most sensitive layer while keeping costs manageable elsewhere.

Does this eliminate security risks? No. Does it reduce them compared to single-vendor dominance? Marginally. Does it acknowledge that security exists on a spectrum, not as a binary? Yes.

The Legal Framework: POPIA as Imperfect but Real Protection

South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), enacted in 2021, is often oversold as a game-changer. It’s not. It’s GDPR-lite with limited enforcement capacity.

But here’s what POPIA does provide:

- Legal basis for data audits: Regulators can require vendors to demonstrate data protection standards, creating a paper trail for accountability

- Cross-border transfer restrictions: Personal data can’t flow to jurisdictions without “adequate protection,” giving regulators leverage over foreign vendors

- Fines and penalties: Up to R10 million or 4% of annual turnover for violations (though enforcement remains patchy)

The weakness? South Africa’s Information Regulator is chronically underfunded and understaffed. As of 2024, the office had fewer than 50 employees to oversee compliance across every sector of the economy. Auditing complex telecom networks for backdoors or data exfiltration requires specialized technical expertise the regulator simply doesn’t have.

The realistic assessment: POPIA creates a regulatory framework for data sovereignty. But frameworks without resources are just paperwork. South Africa needs to invest in cybersecurity capacity—or its legal protections remain theoretical.

The BRICS Factor: Alignment Disguised as Non-Alignment

South Africa’s rhetoric emphasizes “digital non-alignment” and “balancing East and West.” The economic reality is more straightforward: China is South Africa’s largest trading partner, and antagonizing Beijing would have consequences far beyond telecom.

During the 2023 BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, President Cyril Ramaphosa stressed “digital cooperation that respects sovereignty.” But sovereignty, in this context, means accepting Chinese investment while maintaining enough regulatory distance to satisfy Western partners.

This isn’t unique to South Africa. Most emerging economies practice some version of hedging—taking Chinese infrastructure financing while keeping diplomatic channels open to the West. The difference is that South Africa has slightly more regulatory capacity to enforce transparency requirements.

The honest framing: South Africa isn’t pioneering “digital non-alignment.” It’s managing dependencies with China while trying not to burn bridges with the West. That’s realpolitik, not innovation—but it’s realpolitik with some legal guardrails, which is more than many African countries can claim.

Comparative Perspective: The Spectrum of Constrained Choices

Let’s compare how African countries with similar constraints have approached 5G:

| Country | Primary Vendor | Diversification? | Legal Framework | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | Huawei (via Safaricom) | Minimal | Weak data protection law | Rapid rollout, high dependency |

| Nigeria | Huawei + Ericsson split | Yes, but ad hoc | Draft data protection bill | Mixed vendor base, limited oversight |

| Ethiopia | Huawei/ZTE monopoly | None | No data protection law | Fast deployment, total vendor lock-in |

| South Africa | Huawei (RAN) + Ericsson/Nokia (core) | Structured by network layer | POPIA (2021) | Moderate rollout, managed risk |

South Africa’s approach isn’t radically better—it’s incrementally better. The combination of vendor mixing, legal framework (however weak), and public transparency creates some accountability that other markets lack.

What Realistic Alternatives Existed?

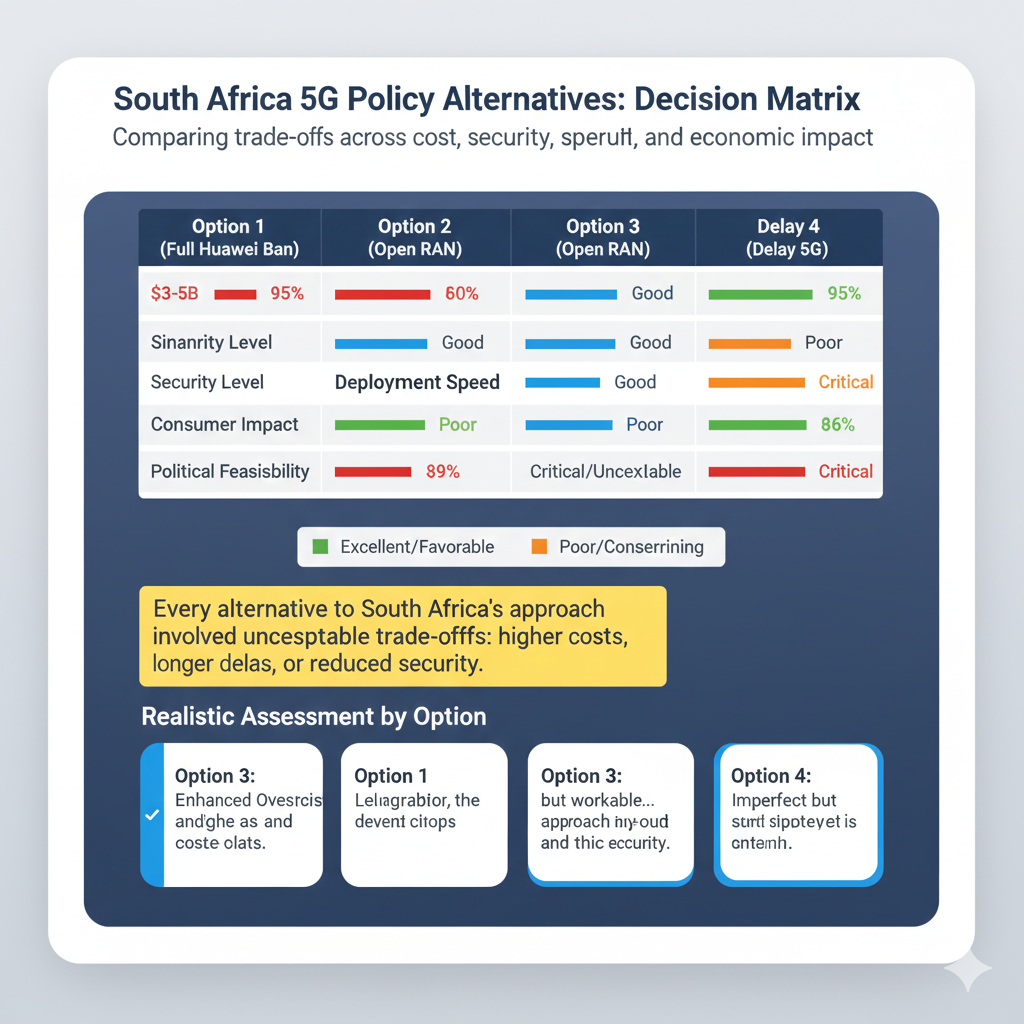

Critics of South Africa’s approach rarely propose viable alternatives. Let’s examine the options honestly:

Option 1: Full Huawei Ban (Australia/UK Model)

Pros: Maximum security control

Cons:

- Estimated cost: $3–5 billion in replacement infrastructure

- 4–6 year deployment delay

- 35–50% increase in consumer data prices

- Loss of vendor financing (Chinese banks provide favorable credit terms)

- Political backlash from China (trade retaliation, reduced investment)

Verdict: Financially catastrophic for South Africa. Only viable for wealthy nations with mature digital infrastructure and access to cheap capital.

Option 2: Open RAN (Japan/Rwanda Model)

Pros: Vendor-neutral standards, future flexibility

Cons:

- Technology still immature (higher failure rates, integration complexity)

- Limited vendor ecosystem in Africa

- Requires significant technical expertise to deploy

- Currently 20–30% more expensive than traditional RAN

Verdict: Promising long-term, but not a 2025 solution. South Africa could pilot Open RAN in select regions while relying on traditional vendors for mass deployment.

Option 3: Status Quo with Enhanced Oversight (South Africa’s Actual Choice)

Pros: Maintains affordability, leverages existing infrastructure

Cons:

- Security risks remain (though segmented)

- Dependency on Chinese vendors continues

- Requires enforcement capacity South Africa struggles to provide

Verdict: Imperfect but workable given constraints. Success depends on strengthening regulatory oversight—the weakest link in the current model.

Option 4: Delay 5G Until Better Options Emerge

Pros: Avoids lock-in to current vendors

Cons:

- South Africa falls further behind in digital competitiveness

- Businesses and consumers lose access to 5G applications (IoT, telemedicine, remote work)

- Regional competitors (Nigeria, Kenya) gain advantage

Verdict: Not viable. Digital infrastructure gaps compound over time; waiting means falling behind irreversibly.

The Real Weakness: Enforcement and Oversight Capacity

South Africa’s biggest vulnerability isn’t its 5G strategy—it’s whether the state can actually implement that strategy.

Capacity gaps include:

- Cybersecurity expertise: The State Security Agency’s cybersecurity unit is understaffed and lacks specialized telecom auditors

- Regulatory resources: ICASA (the telecom regulator) and the Information Regulator operate on shoestring budgets

- Coordination failures: Public-private cybersecurity coordination is ad hoc and fragmented

- Incident response: No unified national cyber incident response framework exists

“We have the policies on paper. What we lack are the people, tools, and budgets to enforce them,” a former ICASA official told TechCentral in 2024.

What would meaningful oversight require?

- Dedicated telecom security auditors: Teams with clearance and technical skills to inspect vendor equipment and software

- Real-time network monitoring: Systems that can detect anomalous data flows or unauthorized access attempts

- Transparent incident reporting: Requirements for operators to disclose security breaches publicly

- Regional cooperation: Sharing threat intelligence with neighboring countries facing similar vendor dependencies

The investment needed: Conservatively, $50–100 million annually for the cybersecurity and regulatory apparatus to function credibly. That’s less than 1% of the replacement cost of a full Huawei ban—but it’s still money South Africa’s fiscally strained government struggles to allocate.

The Load-Shedding Reality: Infrastructure Under Stress

South Africa’s rolling blackouts (“load shedding”) complicate any 5G discussion. When the grid fails, base stations run on backup batteries (4–8 hours) or diesel generators (expensive and polluting).

Impact on 5G deployment:

- 20–30% additional capex for backup power at each site

- Higher operating costs: Diesel fuel, battery replacements, generator maintenance

- Network unreliability: Extended outages drain backup systems, causing service interruptions

Ironically, Huawei’s equipment has proven more power-efficient than some European alternatives—offering 15–20% lower energy consumption per site. In a country where electricity is unreliable and expensive, this matters.

The catch-22: The vendor offering the best solution for power constraints is also the one Western governments consider a security risk.

South Africa’s Just Energy Transition program aims to co-finance renewable power for telecom sites, but progress has been slow. Until the energy crisis is resolved, operators will prioritize equipment efficiency over geopolitical preferences.

What Makes South Africa’s Approach Worth Studying?

Not because it’s ideal—but because it’s replicable under similar constraints. Here’s what other African countries can learn:

1. Segment Risk by Network Layer

If you can’t afford to ban vendors entirely, restrict them from the most sensitive parts of the network. Core infrastructure should prioritize trusted vendors; RAN can tolerate more diversity.

2. Legislate Data Protection Early

Even imperfect laws like POPIA create a framework for future enforcement. Waiting until infrastructure is fully built makes regulation exponentially harder.

3. Demand Transparency from Operators

Publish spectrum allocations, license conditions, and vendor contracts. Public scrutiny creates accountability even when enforcement is weak.

4. Invest in Regulatory Capacity

Policies without enforcement are theater. Budget for cybersecurity auditors, network monitoring tools, and regulatory staff training.

5. Plan for Vendor Transition

Even if you can’t afford to remove Chinese vendors today, plan for gradual diversification. Open RAN pilots, local integration expertise, and skills development reduce future dependency.

Security vs. Connectivity Trade-Offs Are Real

Western governments urging African countries to ban Huawei rarely acknowledge the trade-offs involved. For them, security is paramount because connectivity is already universal. For South Africa, the calculation is reversed: Without affordable connectivity, millions remain digitally excluded—which is its own kind of national security threat.

Consider:

- Economic growth: 5G enables remote work, e-commerce, digital finance, and smart agriculture. Delaying it costs GDP points annually.

- Healthcare access: Telemedicine requires reliable mobile broadband. In rural areas, 5G is the only realistic option.

- Education: Online learning depends on network availability. COVID-19 exposed how digital gaps exacerbate inequality.

- Public safety: Emergency services, disaster response, and law enforcement increasingly rely on real-time data connectivity.

The question isn’t whether Huawei poses security risks—it does, like any vendor with ties to a geopolitical rival. The question is whether those risks outweigh the harm of delayed connectivity for millions of people.

South Africa’s implicit answer: No, they don’t. And for a developing country with limited capital, that’s a defensible position—even if uncomfortable for Western security establishments.

Regional Implications: Why Other African Countries Are Watching

South Africa’s model matters because it’s the closest thing Africa has to a middle path between full Chinese dependency and unaffordable Western alternatives.

Countries watching closely:

- Nigeria: Split its 5G licenses between Huawei and Ericsson but lacks South Africa’s legal framework. Considering POPIA-style legislation.

- Kenya: Safaricom’s Huawei-powered network dominates, but regulators are exploring vendor diversity requirements.

- Ghana: Planning 5G auctions; government officials visited Pretoria to study POPIA implementation.

- Botswana and Namibia: Smaller markets with limited leverage; looking to South Africa for regional coordination on standards.

South Africa’s real influence isn’t its strategy—it’s the precedent of having a strategy at all. Most African countries award telecom contracts through opaque negotiations with little public oversight. South Africa’s approach, for all its flaws, involves:

- Parliamentary hearings on 5G security

- Published spectrum auction terms

- Legal requirements for vendor accountability

- Public debate about trade-offs

That transparency, however imperfect, is the model’s most exportable feature.

The Next Frontier: Cloud, AI, and Data Sovereignty

As Africa moves beyond connectivity infrastructure into cloud computing and artificial intelligence, vendor dependencies will shift—but won’t disappear.

South Africa already hosts:

- Huawei Cloud’s largest African data center (Johannesburg)

- Microsoft Azure’s African regions (Cape Town, Johannesburg)

- Amazon Web Services infrastructure (Cape Town)

- Google Cloud presence (planned expansion)

The next battleground isn’t who builds the networks—it’s who controls the data flowing through them.

South Africa’s draft National Cloud Policy (expected 2025–2026) will attempt to govern:

- Data localization requirements (must certain data types stay in-country?)

- Cross-border data transfer rules (under what conditions can data leave South Africa?)

- Foreign ownership limits for data centers

- Security standards for cloud service providers

The challenge: Overly strict localization requirements could drive investment away; too-lenient rules could leave data vulnerable. South Africa must balance sovereignty with economic pragmatism—the same tension that defined its 5G strategy.

Five Honest Policy Recommendations for African Governments

1. Acknowledge Constraints Publicly. Stop pretending vendor bans are realistic options. Frame the choice honestly: managed risk vs. unmanaged dependency. Public understanding of trade-offs builds support for imperfect policies.

2. Prioritize Regulatory Capacity Over Symbolic Gestures. A $10 million investment in cybersecurity auditors does more for security than a ban you can’t afford to enforce. Build the enforcement apparatus before announcing restrictions.

3. Use Procurement as Leverage. Require vendors to:

- Establish local R&D centers

- Transfer knowledge through university partnerships

- Submit to third-party security audits

- Provide source code access for core network components

If vendors refuse, disqualify them. This creates accountability without full bans.

4. Plan Multi-Year Vendor Transitions. Even if you can’t afford to replace Chinese vendors today, contract terms should allow for gradual migration. Include exit clauses, interoperability requirements, and technology transfer provisions.

5. Coordinate Regionally. Small African markets have little leverage individually. But a regional framework—standardized security requirements, joint procurement, shared threat intelligence—could shift negotiating power toward African governments.

What this might look like: An African Union-backed “Digital Infrastructure Standards Framework” that sets baseline security requirements for any vendor operating in member states. Vendors who comply get preferential access to multiple markets; those who don’t face coordinated restrictions.

Pragmatism, Not Perfection

South Africa’s 5G strategy isn’t a model of digital sovereignty—it’s a model of constrained pragmatism. The country couldn’t afford the luxury of choosing security over affordability, so it tried to balance both imperfectly.

Does this approach eliminate risks? No.

Does it manage them better than single-vendor dependency? Marginally.

Could it work for other African countries with similar constraints? Yes—if they invest in the regulatory capacity to make it real.

The uncomfortable lesson: For developing countries, digital infrastructure involves trade-offs that wealthy nations don’t face. Security is important, but so is access. Legal frameworks matter, but so does enforcement capacity. Vendor diversity reduces risk, but only if you can afford it.

South Africa’s path isn’t heroic—it’s necessary. And necessity, managed with transparency and legal guardrails, is worth studying. Not because it solves the problem, but because it’s honest about what solving the problem would actually cost.

As Africa continues building its digital future, the South African experience offers one clear takeaway: There are no perfect choices. But there are informed ones—and that has to be enough.

Acknowledgment: This analysis benefits from examining the economic and security constraints South Africa actually faces, rather than the policy options available to wealthier nations. The goal isn’t to celebrate South Africa’s choices, but to understand them—and assess whether they’re replicable for countries navigating similar pressures.