How Abuja’s failed CCTV deal exposes the hidden costs of Africa’s digital partnerships with China—and the playbook to fix them.

As of Q4 2025, Nigeria continues to repay a $470 million China Exim Bank loan for a National Public Security Communications System (NPSCS) that lawmakers describe as largely non-functional.

This article unpacks how that happened, how it fits into China’s wider Digital Silk Road strategy, and what African policymakers must change before signing the next “smart city” deal.

Inside Abuja’s Dark Command Center

Walk into Nigeria’s $470 million security command center in Abuja today and you’ll see mostly black screens. The cameras are dead. The debt is not.

The NPSCS, financed by China Exim Bank and executed by ZTE Corporation, was designed to deploy 2,000 CCTV cameras across Abuja and Lagos. But investigations and parliamentary probes revealed that by 2017, only about 40 of Abuja’s 1,000 cameras were working. Performance has deteriorated further since, with the entire system struggling to achieve meaningful uptime.

What Abuja Paid For

In 2010, Nigeria signed a $470 million contract that included:

- 2,000 digital CCTV cameras

- 37 switch rooms and backbone connections

- A central command center

- Emergency response systems and e-police platforms

- 1.5 million Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) lines meant to generate revenue

China Exim Bank covered 85% ($399.5 million) through a Preferential Buyer’s Credit, while Nigeria provided the remaining 15% counterpart funding. By 2020, roughly $307 million in principal was still outstanding, even though the system was barely functional. Nigeria continues to service this loan for an essentially dead asset.

The financing was structured as a soft loan with concessional interest rates, typically with a long repayment period (e.g., 10 years of grace followed by 10 years of repayment). The arrangement, typical of Chinese infrastructure financing, stipulated that a Chinese company would execute the project.

What Went Wrong With Abuja’s $470M Camera System

1. The Cameras Worked Briefly. Then Failed

Initial rollout succeeded, but the system quickly collapsed due to:

- Cameras lacking reliable power supply.

- Widespread vandalism.

- Spare parts being unavailable.

- Poor integration with core policing workflows.

By 2017, only 4% of Abuja’s cameras were operational

2. Maintenance Funding Collapsed

There was no sustained budget for:

- Generator fuel.

- Technical support and spare parts.

- Preventive maintenance contracts.

A government committee found the control room intact. But “nothing functioning,” not even stable power.

3. Procurement and Oversight Failures

Nigeria’s Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) did not issue a “certificate of no objection,” suggesting severe due process irregularities. Civil society had to sue the government before any expenditure details were publicly released, highlighting a deep lack of transparency.

4. Single-Vendor Dependency: Built to Be Obsolete

The system utilized ZTE’s proprietary CDMA (GoTa) technology, which was rapidly being phased out globally in favor of 4G/LTE. This accelerated obsolescence compounded the lock-in problem, making maintenance expertise and parts scarce much faster than anticipated.

5. Debt Outlived the System

Despite extensive downtime and years of dysfunction, Nigeria continues to service the Exim Bank loan. Lawmakers now describe the project as a “non-operational system that still incurs debt obligations.”

Where Abuja Fits in China’s Digital Silk Road Strategy

The Abuja CCTV network aligns perfectly with China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR), the technology pillar of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Across Africa, Chinese telecom firms dominate:

- Roughly 70% of 4G networks are built by Huawei or ZTE

- More than 40 national networks across 30+ African states use Chinese equipment

For Beijing, Nigeria is a strategic anchor: a massive market, an oil supplier, and Africa’s largest population. Even when projects underperform, they succeed in locking in China’s long-term technological and financial influence.

How China’s Concessional Tech Loans Work

China Exim Bank and China Development Bank use a set of standard loan features:

- Maturities: Typically 15–20 years.

- Grace periods: 5–10 years.

- Tied aid: Projects must use Chinese contractors and equipment (like ZTE).

These loans are faster than Western financing and less politically conditional. But they deepen vendor dependency. When countries struggle, China typically restructures rather than cancels debt, preserving its leverage.

Look at Zambia’s 2023 debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework. Official creditors, including China, agreed to extend maturities by more than 12 years and cap interest at 1–2.5% for over a decade. The deal delivered around $5 billion in debt-service savings between 2023 and 2031, but little outright cancellation.

The signal is clear:

China prefers to stretch repayments, not write loans off.

For digital projects like Abuja’s, that means the loan lives on even when the hardware dies.

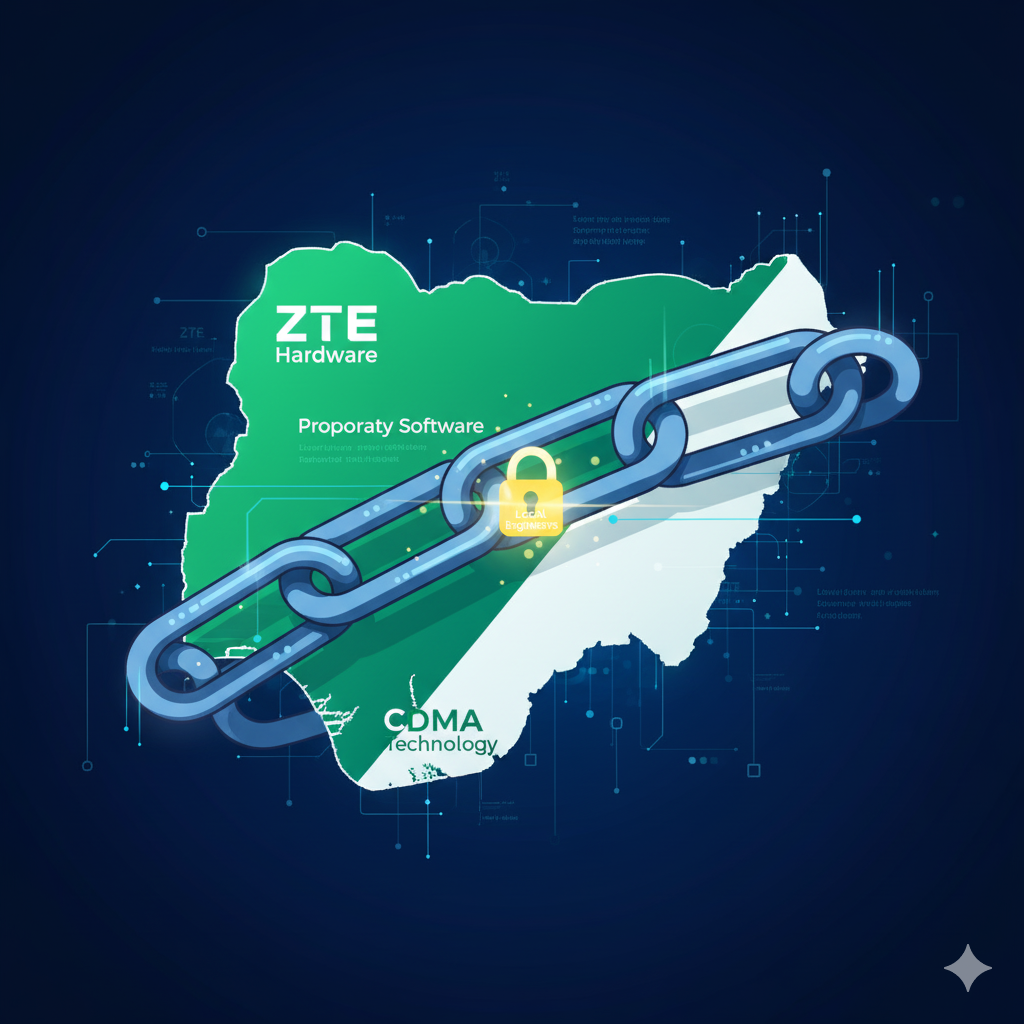

The Technology Trap: Dependency by Design

Infographic depicting a technology chain locking down a map of Nigeria, symbolizing ‘vendor lock-in’ due to proprietary Chinese equipment like ZTE’s CDMA system.

Abuja’s system is built entirely on ZTE’s proprietary architecture, creating multiple layers of dependency:

- Vendor lock-in: Switching vendors requires replacing major hardware components.

- Skills lock-in: Local engineers trained on ZTE cannot easily transition to multi-vendor platforms.

- Weak domestic spillovers: Most funds circulate back to Chinese suppliers, limiting local industry development.

Huawei and ZTE often highlight their training centres and ICT academies across Africa. These programs do create local skills. But research suggests they rarely translate into deep technology transfer or domestic industrial upgrading in countries like Nigeria and Kenya.

Governance and Data Sovereignty Risks

These are Opaque Contracts and Opaque Outcomes. Nigeria did not publicly disclose:

- The full Loan terms

- Value-for-money benchmarks

- Procurement scoring

- Performance metrics

Without transparency, citizens cannot evaluate whether the country achieved value for money, or whether the project was fit for purpose.

The Data Sovereignty Concerns. Nigeria does not publicly confirm:

- Where CCTV footage is stored

- Which agencies access it

- Whether ZTE retains backend administrative privileges

In 2025 hearings, lawmakers could not verify if foreign technicians still held residual access rights. This uncertainty mirrors controversies in Uganda and Zimbabwe, where Chinese surveillance systems raised questions about data control.

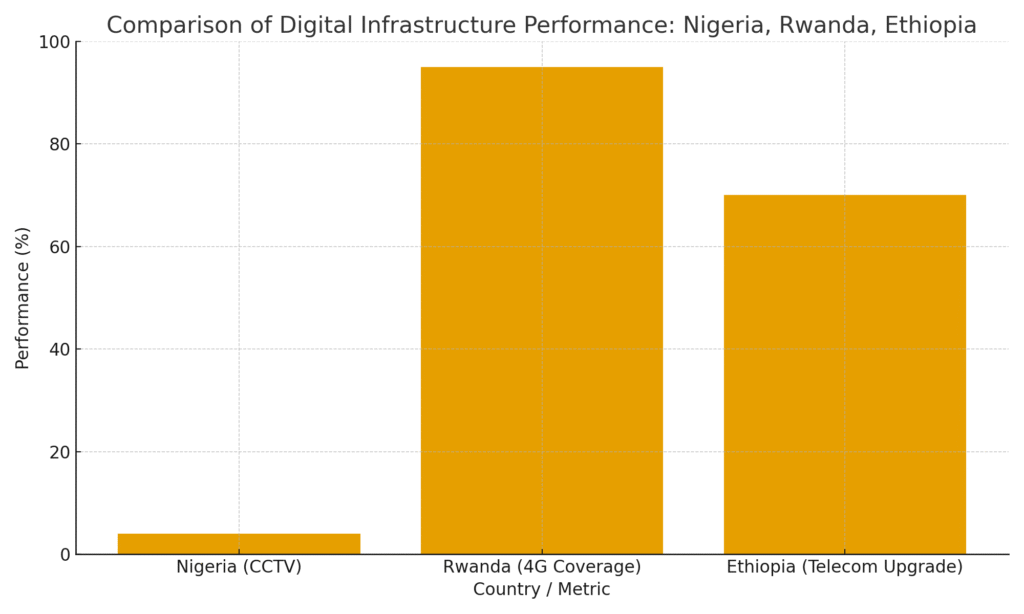

How Ethiopia and Rwanda Managed Their Digital Partners Better

Ethiopia: Centralized Procurement and Training

Through its state-owned operator, Ethio Telecom, Ethiopia negotiated a $1.6 billion nationwide telecom expansion with Huawei and ZTE.

Key advantages:

- One unified implementing institution

- Institutionalized technical training via ICT academies

- Linked rollout schedules and capacity-building milestones

Rwanda: Vendor Diversification and Measurable Coverage Targets

Rwanda partnered with Korea’s KT Corp for its 4G backbone and achieved 95% population coverage by 2018. Chinese firms play supporting roles, but the ecosystem is diversified.

Contrast With Nigeria: Nigeria spent $470 million and ended up with fewer than 40 functioning cameras at one point—effectively over $235,000 per working camera. Ethiopia and Rwanda secured clearer performance metrics and far broader system coverage for their investments.

China’s Perspective: “We Built What You Asked For”

1. Host-Country Responsibility. China frequently argues that systems are built to specification and that maintenance failures are domestic issues, not limitations of Chinese technology.

2. “Our Financing Is Faster and More Practical”. Chinese statements and BRI white papers often emphasize “win-win cooperation” and contrast their rapid delivery with Western institutions.

3. Technology Is Neutral—Governance Determines Misuse. Beijing maintains that Chinese surveillance tools do not inherently enable authoritarianism; misuse reflects local political choices.

What Future Deals Must Fix

1. Transparency as Non-Negotiable: Publish procurement documents and loan contracts, and require independent audits at each milestone.

2. Hard-Wired Performance Metrics: Define strict uptime requirements (e.g., 95% of cameras functional) and tie disbursements to verified technical performance.

3. Vendor Diversity and Interoperability: Avoid single-vendor contracts for critical systems; use open technical standards to prevent lock-in.

4. Technology Transfer With Teeth: Set measurable training targets, require partnerships with Nigerian institutions, and enforce penalties for non-delivery.

5. Data Sovereignty and Protection: Update Nigeria’s data-protection framework, define access, ownership, and retention rules, and localize sensitive video and biometric data.

6. Regional Coordination: Create an ECOWAS Digital Contract Repository, share pricing benchmarks, and reduce vendor information asymmetry

7. Debt Sustainability Filters: Forecast long-term maintenance realistically

and ensure digital loans do not crowd out social spending. Also, reject high-O&M projects unsuited to local capacity

Three Questions Nigeria Must Ask Before Signing the Next Digital Deal

- If this system fails in 10 years, does repayment still make sense?

- If the vendor withdrew tomorrow, could we operate it ourselves?

- If future leaders misuse this technology, would citizens be protected?

From Dead Cameras to Digital Sovereignty

Abuja’s CCTV project is not a reason to avoid Chinese partnerships, but a case study in how to negotiate them better. Nigeria’s next digital deal must begin with published contracts, enforceable performance milestones, data protection laws, and vendor diversification.

The cameras may be dead. But the blueprint for better deals is alive.

FAQ

Why did Nigeria’s Chinese CCTV cameras stop working?

The system suffered from poor maintenance, unstable power supply, limited integration into police workflows, and the quick obsolescence of the proprietary CDMA technology used by the vendor, ZTE.

Who financed the Abuja CCTV project?

China Exim Bank financed 85% of the system through a Preferential Buyer’s Credit tied to the Chinese contractor, ZTE.

What risks come with single-vendor surveillance systems?

They create vendor lock-in, skills dependency, long-term maintenance challenges, and expose the host country to the risk of technology becoming obsolete prematurely (especially with proprietary systems like CDMA).

How does Abuja’s CCTV project fit into China’s Digital Silk Road?

It reflects China’s strategy of exporting digital infrastructure, finance and embedding long-term technological influence across Africa.