When people think of China in Africa, they picture roads, railways and massive ports. That’s part of the story. But there’s another revolution happening right now, and it’s quieter, deeper, and way more consequential. It’s China’s digital footprint in Africa.

The New Digital Silk Road

From 5G networks to smart cities to the cloud infrastructure storing your government’s most sensitive data, China’s basically hardwiring itself into Africa’s digital backbone. It’s branded under the “Digital Silk Road,” the tech arm of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. What’s happening is nothing short of a fundamental reshaping of how Africans connect, communicate, and even govern.

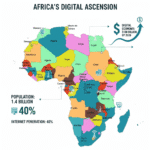

Huawei and ZTE dominate Africa’s telecom landscape. Over 70% of Africa’s 4G infrastructure has Chinese involvement. Huawei alone operates in more than 40 African countries—one company touching the digital lives of 1.4 billion people across an entire continent.

Here’s What Nobody Really Talks About: Control

Finance: China has extended over $182 billion in loans to 49 African countries and regional organizations since 2000, making it a leading lender to the continent.

Surveillance systems: Beijing has deployed smart city surveillance systems in at least nine African countries, integrating CCTV, biometrics, and AI for urban management and security.

Digital identity databases: China’s technology and investments help many African states establish and upgrade their digital ID systems, increasingly critical for government operations.

The cloud infrastructure that’ll power Africa’s artificial intelligence revolution.

While these projects boost connectivity and innovation, they also raise vital questions about data sovereignty, cybersecurity, and technological independence—reshaping the balance of digital power across the continent.

Telecommunications Infrastructure—Connectivity as Strategic Leverage

If you want to dominate a continent’s digital future, you need to own the pipes that carry the data. Huawei and ZTE have built and upgraded thousands of kilometers of fiber optic cables, mobile base stations, and 5G towers across Africa. They’re laying the electrical wiring for an entire continent’s digital nervous system.

Kenya: The 5G Pioneer and the M-Pesa Connection

Kenya shows you how this actually works in practice. Huawei is deploying 5G towers and is central to Konza Technopolis, Kenya’s smart city project 60 kilometers southeast of Nairobi.

Konza Technopolis Update (2025): After years of skepticism and “white elephant” accusations, Konza is finally showing concrete progress. In October 2025, Kenya officially launched Phase 1 of the horizontal infrastructure—roads, water systems, wastewater reclamation facilities, and utility tunnels. The project secured a $284.1 million financing agreement with South Korea for a Digital Media City, and Kenya approved the Konza National Drone Corridor, Africa’s first controlled airspace for commercial drone operations.

However, challenges persist: billions in idle technology equipment sit unused (only 1,000 of 17,508 deployed virtual desktop devices are active), and only 33 of 515 surveyed land parcels have been leased, with just 9 developed by the end of 2024. The project generated just $1.96 in annual revenue against cumulative investment of $646.9 million.

The M-Pesa Story Nobody Tells:

Huawei partners with Safaricom to manage the underlying infrastructure for M-Pesa, the mobile money system that over 50 million customers across eight African countries depend on. Since migrating M-Pesa to the Huawei Mobile Money Platform in 2014, Huawei has been instrumental in enabling microloans, scaling across multiple countries, and maintaining high availability for tens of millions of users.

When you send money on M-Pesa, you’re literally using Chinese-built technology. That’s deep integration nobody talks about. The platform works on both smartphones and feature phones, provides encryption technology and carrier-grade infrastructure, and has been key to M-Pesa’s explosive growth—now responsible for 40% of Safaricom’s revenue, up from 20% in 2014.

Ethiopia’s Big Bet: The Deepest Dependency

Ethiopia spent $1.6 billion on telecom modernization with equipment from ZTE and Huawei. The government’s also rolling out a digital ID system, another Chinese-backed project. On the surface, this seems great: modernized telecoms, better government services.

But think about what happens next: Ethiopia’s telecom infrastructure is now dependent on Chinese vendors for maintenance, upgrades, and spare parts. ZTE served as Ethiopia’s exclusive telecom equipment supplier from 2006-2009, building the foundation of the national network.

Important context: China is the single largest source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Ethiopia. As of mid-2024, of the roughly $3.9 billion in FDI Ethiopia attracted, nearly 50% came from Chinese companies.

Nigeria: The Quiet Expansion

Nigeria’s different. It’s not waiting for big government contracts. Chinese companies are already woven into Nigeria’s private telecom sector, extending coverage to rural areas that Western companies deemed unprofitable. ZTE’s doing most of this work. It’s a smart strategy: get into the places nobody else wants to go, become essential, and then you’ve got a permanent foothold.

The Internet Growth Story That Changed Everything

The number that matters: internet penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa was around 12% in 2015. By 2023, it was over 35%. That’s a massive jump, and Chinese equipment played a huge role.

But let’s be real about what comes with it: dependency. African countries now rely on Chinese vendors for maintenance, hardware upgrades, cybersecurity systems—everything. If something breaks, you call Huawei or ZTE. If you need a security patch, you wait for Beijing to provide it. That’s not necessarily malicious, but it does mean China has leverage.

Digital Finance and E-Payments—The Fintech Revolution

Africa has this interesting position in the global economy. It didn’t develop banking infrastructure the same way Europe did. That meant when mobile money came along, it leapfrogged the whole banking system. Now China’s looking at this and thinking: “We can control this too.”

How the Money’s Actually Moving

Ant Group (which owns Alipay) and Huawei Pay have signed agreements with African banks and telecom companies to enable cross-border payments and e-wallets. In Kenya, they’ve integrated with M-Pesa to make it easier to send money between Africa and China. That seems convenient, right? And it is.

But it also means that transaction data, payment patterns, user information—all of it flows through systems ultimately controlled by Chinese companies.

Think about this: if you’re a small business owner in Kenya using M-Pesa to buy from a Chinese supplier, that entire transaction chain is visible to Chinese fintech companies. That’s valuable competitive intelligence.

PalmPay and OPay: The Real Story

PalmPay and OPay are the names you should know. PalmPay, backed by Chinese investors, hit 10 million users in Nigeria by 2022. OPay, also Chinese-backed, is doing even better in some markets. They’re fundamentally changing how Nigerians buy things online, send money, and borrow money.

Why this matters beyond payment processing: These apps offer microloans. You download the app, use it a few times, and suddenly the algorithm decides you’re creditworthy and offers you a loan. No bank visit. No paperwork. Just instant credit.

Sounds great, and for millions it’s transformative. But here’s the thing: these algorithms are opaque. You don’t know how they’re evaluating you. You don’t know if they’re using race, gender, location, or other sensitive factors. And there’s basically no regulatory oversight.

The Privacy Problem

These platforms excel at financial inclusion, which is real and important. But they’re also collecting massive amounts of personal data: financial history, location data, phone contact lists—everything. In many African countries, data protection laws barely exist or aren’t enforced.

The question keeps coming back: if I’m a poor farmer in Nigeria using an app to get microloan, am I getting access to credit and economic opportunity, or am I just feeding data into a surveillance machine? Probably both, honestly.

Smart Cities and E-Government—Efficiency and Surveillance

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable. China’s exporting its entire approach to city management, including surveillance systems that would make most Western democracies nervous.

The Cameras in Kampala

Uganda deployed Huawei’s “Safe City” system for security and surveillance. In Kampala alone, that’s over 3,000 CCTV cameras integrated into a centralized monitoring system. Connected to a system that can identify faces, track movements, flag suspicious behavior based on algorithms you can’t audit or question.

The government says it’s for security. And maybe some of it is. Fewer criminals operate when they know they’re being watched. But those same cameras can track protesters, monitor ethnic minorities, suppress dissent, or conduct broad-based surveillance. History shows us that happens.

Ethiopia’s doing the same thing with Huawei’s Safe City platform. Zambia and Cameroon have Chinese-built ICT platforms for government services. On the surface, this is great: citizens can get permits and licenses online instead of dealing with corrupt officials. But these systems also collect data going to servers controlled by Chinese companies.

The Efficiency vs. Freedom Trade-off

Here’s the uncomfortable truth nobody wants to say out loud: these systems actually work. They make cities cleaner, safer in some ways, more efficient. Traffic moves better. Crime goes down in monitored areas. Government services get faster. People like this stuff.

The problem is that convenience comes with a surveillance state attached. It’s the model China uses at home—citizens have less privacy, but public services are efficient and reliable. And now countries like Uganda and Ethiopia are adopting the technology without necessarily adopting oversight mechanisms or transparency requirements.

We’re basically seeing an export of a governance model, not just technology. And most people don’t realize that’s happening.

Cloud Computing and Data Centers—The Infrastructure of AI

Remember when data used to be stored on servers in your country? Not anymore. Now it’s floating somewhere in the cloud—which is just somebody else’s computer. And increasingly, that computer is owned by Chinese companies.

Where Africa’s Data Is Going

Huawei Cloud and Tencent Cloud have launched data centers in South Africa and Egypt. These aren’t small operations—we’re talking multi-million-dollar investments with capacity to store petabytes of data. Government records, business data, personal information—everything stored in Chinese-managed systems.

Recent developments: In December 2025, South Africa’s Broadband Infraco (BBI) partnered with Huawei to build a national intelligent all-optical backbone network using 800G wavelength technology. The infrastructure has connected over 13,000 public Wi-Fi hotspots and more than 2 million homes in rural areas.

In November 2024, MTN South Africa signed an MoU with China Telecom Global and Huawei to develop digital infrastructure across MTN’s African footprint, focusing on 5G, cloud, AI, and enterprise solutions.

The theory is that this keeps data local and creates African tech infrastructure. The reality is more complicated. Yes, the servers are physically in South Africa or Egypt. But the software running them, the security protocols, the access logs, the ability to move or copy that data somewhere else—that’s all controlled by Chinese companies.

The Data Sovereignty Question

Here’s what keeps tech policy people up at night: who actually controls your data? In theory, it’s the government or company that owns it. In practice, whoever owns the infrastructure that stores it has enormous leverage.

If Egypt’s government stores critical infrastructure data in a Huawei server, and China says “we need that data,” what exactly is Egypt supposed to do?

This isn’t paranoid speculation. This is the kind of thing that happens in international relations. Countries use control of infrastructure as leverage. By building data centers in Africa, China’s creating leverage over African nations’ most sensitive information.

Strategic Motives Behind Beijing’s Expansion

Why’s China doing this? It’s not charity. Let’s think through the actual motives.

1. Economic Leverage

By dominating Africa’s telecom sector, China ensures African companies need to buy Chinese equipment and services. Huawei and ZTE are basically extensions of state power—not independent private companies in the way Western tech companies pretend to be.

2. Setting the Rules of the Game

China’s essentially setting technical standards. When African countries adopt Chinese technology, they also adopt Chinese technical standards. Not necessarily by choice, but because that’s what their infrastructure uses.

When you set the technical standard, you have enormous power because everyone else has to build around it. Western companies now have to build technology that works with Huawei infrastructure, accommodating Chinese designs, Chinese security protocols, Chinese ways of thinking about data.

Eventually, this becomes the norm. It’s just how things work.

3. Soft Power and Influence

Huawei runs ICT academies across Africa, training African tech professionals. Scholarships bring African engineers to China to study. This builds relationships, creates people sympathetic to China, creates networks.

When someone’s studied in China, learned Mandarin, made friends there, they’re more open to Chinese technology and investment. That’s not manipulation—that’s just how human relationships work. But on a scale across a continent, it’s incredibly powerful soft power.

4. Geopolitical Positioning

The US has been focused on the Middle East for decades. Europe’s obsessed with its own problems. China looks at Africa and sees a continent with a billion people and tremendous resources that’s been left underinvested.

By providing infrastructure, by being present, by becoming essential, China builds relationships and influence. If there’s a UN vote or a geopolitical crisis, China’s got friends in Africa. It’s not overtly military—it’s structural. But it works.

The Belt and Road Financing Model: Understanding the Debt Trap Risk

Here’s the thing about Chinese infrastructure investments most people don’t understand: the money’s not free. It usually comes with strings attached.

How the Loans Actually Work

Most digital projects are financed through loans from China Exim Bank or China Development Bank. These are banks, not charities. They expect to get paid back.

The loans appear reasonable on the surface: lower interest rates than Western banks, longer repayment periods. African governments think “Great, we can afford this.” But there’s usually a condition: you have to hire Chinese companies to build the infrastructure. Specifically, Huawei or ZTE. Those companies then subcontract with other Chinese suppliers. The money flows through the system, and eventually most of it ends up back in China anyway.

The Lock-in Problem

Once you’ve built your entire telecom infrastructure on Huawei equipment, financed by Chinese loans, your government is now paying two streams of money to China:

- Loan repayments

- Ongoing maintenance and upgrade costs

Those costs don’t really end. Infrastructure requires maintenance. Software needs updates. Equipment eventually needs replacement.

You’re essentially locked in. You can’t switch to another vendor without massive additional expense. You can’t reduce dependence on Chinese technology without ripping out and replacing your entire infrastructure.

What Happens When Things Break

Let’s say a country takes a $500 million loan from China Exim Bank to modernize telecom infrastructure. The loan requires hiring Huawei to build it. Equipment costs $300 million. Huawei’s profit is $100 million. The rest goes to various vendors, logistics, installation—but most stays in China.

Meanwhile, the country owes back $600+ million (with interest) over fifteen years.

If revenue doesn’t materialize, or maintenance costs are higher than expected, or there’s an economic recession, that country’s in trouble. Do they default? Cut other spending? Keep paying even though it means less money for education or healthcare?

These aren’t hypothetical questions. African countries are dealing with exactly this situation right now.

The Strategic Lock-in

Once a country is locked into Chinese infrastructure and Chinese debt, Beijing has leverage over your policy. If you’re considering allowing American tech companies to compete, China can remind you you’re their debtor. If you’re thinking about joining a political alliance that opposes China, China can threaten to call in the debt.

Infrastructure becomes a political tool. This isn’t conspiracy theory—this is how international power works.

The African Perspective: Opportunities, Risks, and Digital Sovereignty

Let’s step back and think about this from an African perspective. It’s not all bad. It’s complicated.

Opportunities for African Development

Connectivity That Actually Matters

Millions of Africans have internet access now who didn’t have it five years ago. That’s not trivial. A kid in rural Kenya can now access the entire sum of human knowledge. A farmer in Nigeria can watch YouTube videos about crop rotation, check commodity prices in real-time, connect with markets she never would’ve reached before. That’s transformative. That’s real human benefit.

Jobs, Skills, Actual Opportunities

When Huawei or ZTE sets up a regional hub, they hire local people. They train them. They create a tech ecosystem. Countries like Kenya and Nigeria now have thriving tech sectors that didn’t exist twenty years ago. Thousands of people employed, tens of thousands trained. That’s not propaganda—that’s verifiable economic activity.

Government Actually Works Better

E-government systems reduce corruption. Instead of paying a bribe to a government official, you just go online and process your permit digitally. Services get faster. There’s an audit trail. Citizens know what things actually cost. That’s real improvement in people’s daily lives.

Credit for People Who Were Never Getting Credit

Those microfinance platforms, PalmPay and OPay? They’ve given credit to millions of people who would never get a loan from a traditional bank. A woman running a small grocery store in Lagos can now get working capital for her business through an app. That’s not small. That’s economic freedom for people who didn’t have it.

The Real Risks

You Become a Consumer, Not a Creator

Here’s the long-term problem: if every piece of digital infrastructure comes from China, African countries stop building their own tech capacity. Why invest in developing local software companies when you can just buy cheap Chinese solutions?

But eventually, that means Africa becomes dependent on imported technology, not a creator of technology. And technology is where the money and power are in the 21st century.

It’s like if all of Africa’s cars came from one foreign country: you’re not developing a manufacturing sector, not training engineers, not creating high-wage jobs. You’re just buying.

Your Personal Data Isn’t Protected

Most African countries don’t have strong data protection laws. The ones that do usually don’t enforce them. So if you’re using PalmPay and your data gets shared with Chinese marketing companies, or if Huawei accesses traffic camera footage to identify dissidents, who’s going to stop them? Nobody. There’s no recourse.

This is especially scary with surveillance systems. If Uganda has 3,000 Huawei cameras tracking the city with no oversight, no transparency, no ability for citizens to audit how that data’s being used, then you’ve got a surveillance machine with no checks on it.

You Get Stuck with Other People’s Debt

When you take out a $500 million loan and the economy slows down, you’re in trouble. And you’re in trouble to China specifically, a country with very different foreign policy interests than Western countries. If China decides to pressure you politically, they can leverage your debt. That’s not theoretical—it’s leverage that can be exercised.

Infrastructure Becomes a Geopolitical Vulnerability

Imagine there’s a conflict between Africa and China, or between the US and China, and the US decides to sanction Chinese companies. Suddenly all of Africa’s telecommunications infrastructure is at risk. No parts, no updates, no security patches.

Or imagine China cuts off access to African data as retaliation for some political disagreement. What does Africa do then?

These scenarios seem unlikely now, but they’re the kind of thing that could happen, and if it does, Africa’s in a bad position.

Global Reactions: The Tech Geopolitics of Africa

China’s not the only country that’s noticed Africa’s digital future is up for grabs. This is turning into a real competition.

The Western Alternative: More Expensive, More Principled, Less Practical

The US started initiatives. The EU has its Global Gateway program. The G7 created Build Back Better World. These are supposed to be alternatives to Chinese investment, emphasizing transparency, environmental standards, labor rights, democratic governance. All good things, obviously.

But they’re way more expensive. They come with conditions. They move slower. If you’re an African country that needs telecommunications infrastructure built in the next year, not five years, China’s offering is a lot more attractive than a Western program requiring environmental impact assessments, audits, and compliance certifications.

Also, Western countries are rich, so they have less urgency. China’s desperate to recycle capital, find new markets, expand its sphere of influence. That desperation can look a lot like enthusiasm and partnership.

India’s Playing a Different Game

India’s emerging as an interesting alternative. Indian tech companies are building presence in Africa with a different approach: open-source software, data-sharing initiatives, technology transfer, capacity building. India’s saying: let’s build infrastructure together, let’s transfer knowledge, let’s create local capacity.

It’s a different philosophy. Less extractive. More focused on building up African capacity rather than creating dependency. But India’s also not as rich as China and can’t throw around capital the same way. So it’s attracting a different kind of partnership: countries that want to build tech capacity, not just get infrastructure.

The African Balancing Act

Smart African countries aren’t choosing sides. They’re doing what nations have always done: playing different powers against each other. Kenya accepts Chinese investment but also works with Western companies. Nigeria spreads its partnerships across China, the US, India, everyone. It’s pragmatic. You get the best deal you can from each source, and you avoid letting any single power dominate.

Alternatively, if China’s the only one offering the financing and technology you need, you can’t really negotiate. You take what you can get. So the whole premise of “balanced partnerships” only works if the Western countries are actually competitive.

The Future of Africa’s Digital Sovereignty: Navigating the Crossroads

Africa’s at a crossroads. The digital infrastructure being built right now is going to shape the continent’s future for decades. Get it right and Africa becomes a digital powerhouse. Get it wrong and Africa becomes a digital colony, dependent on external powers for its most critical infrastructure.

What Actually Needs to Happen

African governments need policy frameworks that protect data, enable cybersecurity, and prevent vendor lock-in. That sounds boring and technical, but it’s actually the most important work happening right now.

Data Localization: Some data needs to stay in-country, under local control. Not all data, because that’s inefficient and expensive, but critical data. Government data, health records, financial system data. These should be protected by local law, stored locally, accessible by local authorities.

Surveillance Transparency: If a city’s installing 3,000 cameras, there need to be rules about how that footage can be used, who can access it, how long it’s stored. There need to be independent audits. Citizens need the ability to know what they’re being monitored for and have recourse if it’s abused.

Technical Interoperability: Infrastructure needs to be built in ways that don’t lock in a single vendor. Use open standards. Make it possible to switch to different suppliers without replacing everything. This prevents the kind of dependency we’ve been talking about.

Cybersecurity Requirements: Before deploying critical infrastructure, have independent security reviews. Make sure there are no backdoors, no hidden vulnerabilities, no ways for foreign governments to access systems. This costs money and time, but it’s worth it.

Technology Transfer: When African countries invest in infrastructure, they should negotiate for technology transfer. Train local people to build and maintain these systems. Develop local capacity instead of remaining dependent on foreign experts.

These aren’t anti-China policies. They’re just smart policies that would protect African interests against any foreign power.

The Real Choice

The choice isn’t “Chinese technology or nothing.” The choice is whether Africa becomes a producer of technology or just a consumer. Whether Africa controls its own digital future or outsources it. Whether African data and infrastructure are African assets or just raw material extracted by foreign companies.

The window for making this choice is closing. Every day, more infrastructure gets built, more dependencies get established, more leverage gets built in. In five years, it might be too late. In ten years, it’ll definitely be too late.

Partnership or Dependence? That’s Africa’s Choice

China’s digital footprint in Africa is real. The infrastructure’s being built. The data’s being collected. The relationships are being established. It’s not some future threat—it’s happening now.

Some of it’s genuinely good: People have internet access. They have financial services. Government’s more efficient. That’s real.

But some of it’s genuinely worrying: Surveillance systems without oversight. Data stored in servers owned by foreign companies. Critical infrastructure financed through debt that creates political leverage. That’s real too.

The honest truth is that this is going to go both ways. Africa will benefit from Chinese investment. The continent will also become more dependent on Chinese technology and Chinese capital. The question is whether African governments can set up frameworks to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks.

The answer requires:

- Leaders who think long-term instead of just solving immediate problems

- Regulations written by people who understand technology

- Saying no sometimes, even when money’s on the table

- Building local capacity so that China isn’t the only option

None of that’s happening automatically. It only happens if African governments make it happen.

So the real question isn’t what China’s doing in Africa. China’s doing what makes sense for China.

The real question is: what are African countries going to do about it?

Will Africa’s digital transformation be powered by genuine partnership, or shaped by dependence?

That’s not Beijing’s choice. That’s Africa’s choice. And they need to make it fast.

Key Takeaways

The Scale: Over $182 billion in Chinese loans since 2000, with 70% of Africa’s 4G infrastructure involving Chinese companies.

The Players: Huawei (dominant telecom vendor), ZTE (cost-competitive alternative), China Telecom Global (data highways), Ant Group/Huawei Pay (fintech), CloudWalk (AI surveillance).

The Opportunities: Real connectivity gains, job creation, financial inclusion, improved government services.

The Risks: Technological dependency, debt leverage, surveillance without oversight, data sovereignty concerns, geopolitical vulnerability.

The Choice: Africa must decide now whether to become a technology creator or remain a technology consumer. The window is closing.