The cameras arrived without fanfare and went up quietly.

No national referendum. No citywide debate. In many cases, not even a parliamentary vote. One day, traffic lights adjusted themselves. Police dispatchers watched live feeds from dozens of intersections. Facial recognition software flagged “unusual behavior.”

Across Africa, surveillance-led smart cities have expanded not through public demand, but through procurement decisions, security narratives, and foreign-financed infrastructure deals. And at the center of this expansion sits one dominant supplier: China.

Inside Africa’s Quiet Surveillance Boom

Chinese-built surveillance systems now shape daily life in African capitals and secondary cities alike, promising safety, efficiency, and modernization. But beneath that promise lies a deeper question: who controls the data, the systems, the power these technologies confer? And why Regional Coordination is the only way forward.

Nairobi, Kenya, authorities monitor traffic live feeds in a control center

What’s a Smart City? In theory, smart cities are about efficiency—optimizing traffic flow, reducing emergency response times, and improving urban services. In practice, most Chinese-backed smart city projects in Africa follow a surveillance-first design.

Typical deployments include:

- Dense networks of high-definition CCTV cameras covering major streets, intersections, and public spaces

- Centralized command-and-control centers where authorities monitor live feeds

- AI-powered video analytics capable of facial recognition, behavior detection, and crowd analysis

- Integration with police databases and national ID systems

- Real-time traffic and crowd monitoring linked to enforcement mechanisms

These systems are rarely modular or limited in scope. Once installed, they become permanent urban nervous systems, feeding data into centralized authorities. Unlike consumer-facing technologies, citizens rarely opt in—or out. The infrastructure precedes consent.

The Cross-Border Data Challenge

These systems are not confined by borders—but their regulation is. Data flows across national boundaries through shared telecommunications infrastructure, vendor maintenance networks, and integrated security frameworks. Yet governance remains stubbornly national, creating gaps that grow wider as technology advances faster than policy.

This presents both opportunity and risk. When properly governed, cross-border data sharing can enhance regional security cooperation, disaster response, and economic integration. The challenge lies in building safeguards that travel as freely as the data itself.

Exporting the “Safe City” Model

China’s approach is not accidental. It reflects a governance model refined domestically and exported abroad under the banner of “Safe City” or “Smart City” solutions. The model’s success in Africa stems from more than technological capability—it exploits regulatory fragmentation across regions.

Key suppliers include Huawei, ZTE, Hikvision, and Dahua—firms that offer not just hardware, but entire governance platforms. What African governments buy is a complete stack:

- Cameras, sensors, and physical infrastructure

- Software platforms and AI analytics engines

- Training programs for police and city officials

- Long-term maintenance contracts and system upgrades

The Financing Mechanism

Financing often comes bundled via Chinese state-linked lenders—the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China, or through Belt and Road Initiative frameworks. This reduces upfront costs while locking governments into multi-year obligations. The appeal is immediate: visible infrastructure, rapid deployment, integrated financing. The trade-offs emerge later.

The model succeeds partly because vendors negotiate country by country, tailoring terms to individual political contexts while maintaining technological standardization. No single African state has the leverage to demand fundamental changes to proprietary systems, data sovereignty guarantees, or exit clauses. Regional fragmentation becomes vendor advantage.

Case Studies: Three Cities, Three Models

Nairobi traffic management center.

Nairobi: Surveillance as Urban Management

In Nairobi, Chinese-built surveillance systems are integrated into traffic management, policing coordination, and emergency response. Officials credit the systems with faster incident response times, improved traffic flow during peak hours, and better coordination during public events.

Measurable Benefits

The visible benefits are real and quantifiable. According to Kenya’s National Police Service, response times to traffic accidents decreased by approximately 30% in monitored areas between 2018 and 2022. Traffic violations detected through automated systems increased enforcement consistency, with the National Transport and Safety Authority reporting a 22% reduction in peak-hour congestion at key intersections equipped with smart traffic management.

The command center coordinates multiple agencies from a single location—police, fire services, ambulances, and traffic management—enabling faster crisis response during emergencies and public events. During the 2022 general elections, the integrated system facilitated coordination across security agencies, contributing to one of Kenya’s most peaceful electoral periods in recent history.

The Governance Gap

But civil society groups have raised persistent concerns about accountability:

- Limited transparency on data retention policies—how long footage is stored, who can access historical data, and under what conditions

- Unclear rules on facial recognition use—whether the technology is active, what databases it searches against, and what triggers an alert

- Minimal public oversight mechanisms—no independent body reviews surveillance decisions or investigates misuse complaints

Kenya has data protection laws on paper—the Data Protection Act of 2019 established principles and created an office of the Data Protection Commissioner. But enforcement capacity lags behind technological deployment. Surveillance expanded first. Regulation followed later. And the Commissioner’s office lacks the technical expertise and resources to audit complex AI systems.

Regional Context: As a member of the East African Community (EAC), Kenya’s surveillance infrastructure has implications beyond its borders. The EAC is moving toward integrated digital markets and shared security frameworks. If Nairobi’s systems begin exchanging data with counterparts in Kampala or Dar es Salaam—already under discussion for counterterrorism coordination—the weakest data protection standard becomes the de facto regional standard. Cross-border surveillance requires cross-border safeguards. Neither currently exists.

Addis Ababa: Total Visibility, Minimal Oversight

Ethiopia represents one of Africa’s most comprehensive state surveillance environments. In Addis Ababa, surveillance is tightly woven into national security architecture, linked not just to urban management but to political control.

The system monitors:

- Traffic and public transportation networks

- Crowds at political rallies and protests

- Communications infrastructure through integrated telecom surveillance

- Border crossings and identity verification points

Surveillance infrastructure in Addis Ababa

Chinese Technology Integration

Chinese technology providers—particularly Huawei and ZTE—have played central roles in building these systems, often embedded within broader telecommunications modernization projects. The surveillance layer is rarely itemized separately in contracts; it appears as a component of “public safety infrastructure” or “emergency management systems.”

This integration has delivered operational benefits; improved coordination during public health emergencies, faster identification of traffic bottlenecks, and enhanced border security capabilities. The system’s technical sophistication is undeniable.

Political Control Concerns

However, critics argue that surveillance has been used not just for crime prevention, but for political control during periods of unrest. During the Tigray conflict and subsequent political turbulence, civil society organizations documented surveillance systems tracking opposition figures, monitoring ethnic communities, and coordinating crackdowns on dissent.

The key issue is not whether the technology works—it does, with high technical efficiency. The question is how it is used, and by whom. In the absence of independent oversight, judicial authorization requirements, or transparency obligations, dual-use surveillance becomes an instrument of state power with few checks.

Regional Context: Ethiopia’s dual role as both an AU member state and host to AU headquarters creates a paradox. The African Union has endorsed digital rights principles and data protection guidelines through the Malabo Convention. Yet its host nation operates one of the continent’s most opaque surveillance regimes. This undermines the AU’s credibility in setting regional norms. If surveillance governance standards are not harmonized, member states can point to the disconnect between AU rhetoric and Ethiopian practice to justify their own weak protections.

Kigali: Efficiency with Centralized Control

Kigali is often showcased as Africa’s smart city success story. Clean streets, efficient services, disciplined urban management, and a government that delivers visible results. Surveillance fits seamlessly into this model.

Clean Kigali streets with modern infrastructure and visible smart city elements

The Smart City Infrastructure

Cameras support:

- Automated traffic enforcement with immediate fine processing

- Public order maintenance and rapid response to disturbances

- Citywide environmental monitoring (illegal dumping, sanitation violations)

- Crime prevention through predictable deterrence

Rwanda’s strength lies in state capacity. The government can plan, procure, and implement complex systems effectively. Service delivery is real. Citizens see results. UN-Habitat’s evaluation of Kigali’s Smart City Master Plan highlights achievements in waste management efficiency, traffic flow optimization, and reduced emergency response times.

A Diversified Technology Approach

Importantly, Rwanda’s smart city model involves partnerships beyond China. While Chinese firms like Huawei have contributed to telecommunications infrastructure under the Digital Silk Road initiative, Rwanda has also partnered with Western technology providers for broadband connectivity and smart grid systems. This diversification demonstrates that African states can leverage multiple technology partnerships while maintaining strategic autonomy—though governance challenges remain regardless of vendor origin.

The Governance Trade-Off

Rwanda’s political system offers limited pluralism, restricted press freedom, and constrained civil society space. Smart systems work well—but citizens have few avenues to challenge misuse or demand accountability. As Good Governance Africa notes, “good” surveillance infrastructure can enable repressive governance when institutional checks are absent.

The question is not whether Kigali’s smart city model delivers urban services—it demonstrably does. The question is whether the model can be separated from the political context that enables it. Can surveillance infrastructure built for efficiency avoid becoming infrastructure for control?

Regional Context: Rwanda is a member of both the EAC and COMESA. Its smart city model is being studied and replicated by neighboring states. If surveillance-linked urban management becomes the regional standard without accompanying governance safeguards, the model’s authoritarian elements may spread as readily as its efficiency gains. Regional bodies have an interest in ensuring that what travels across borders is best practice—not just any practice.

The Financing Question: Surveillance by Debt

Surveillance infrastructure rarely appears as “surveillance” in loan agreements or procurement contracts. It is embedded inside broader categories:

- Urban renewal and modernization projects

- National ICT infrastructure upgrades

- Police digitization and capacity-building programs

- Smart transportation and traffic management systems

Hidden Costs and Lock-In

This makes accountability difficult. Surveillance spending is diffused across multiple budget lines, often classified under “security” or “infrastructure,” shielding it from the scrutiny that would accompany a standalone “national surveillance system” appropriation.

Loans tied to these projects are sovereign obligations. Even if a government later decides a system is intrusive, replacing it can be financially and technically impossible. Contracts often include:

- Proprietary software that cannot be modified without vendor approval

- Hardware dependencies that prevent integration with alternative systems

- Long-term licensing and maintenance costs that grow over time

- Training programs that embed vendor-specific knowledge

This creates vendor lock-in—not just technological, but institutional. Surveillance becomes not just a policy choice, but a structural constraint. Future governments inherit systems they cannot easily exit, audit, or replace.

Individual states negotiating alone have limited leverage. Collectively, they could shift terms—demanding interoperability standards, local data hosting requirements, and transferable ownership of software and training capacity. But this requires coordination. And coordination requires regional frameworks that do not yet exist.

Privacy, Power, and Political Leverage

The greatest risk is not mass surveillance itself—though that raises legitimate concerns—but selective surveillance. Tools introduced for crime prevention can be repurposed for political control with minimal technical modification. The same system that tracks stolen vehicles can track journalists. The same facial recognition that identifies wanted criminals can identify opposition activists.

Documented Dual-Use Cases

Civil society organizations have documented instances across the continent including:

- Monitoring political opponents during election periods

- Tracking journalists covering sensitive stories

- Surveilling ethnic or religious communities deemed security risks

- Managing protests through preemptive identification of organizers

These concerns must be balanced against legitimate security needs. Governments face real threats—terrorism, organized crime, cross-border trafficking—that surveillance can help address. The challenge is building systems that serve public safety without enabling political abuse.

The Missing Safeguards

Many African countries lack the institutional safeguards that might prevent misuse:

- Independent data protection authorities with enforcement power

- Judicial oversight requiring warrants for surveillance activation

- Transparency requirements mandating public reporting on system use

- Civilian complaint mechanisms with investigative authority

Without these safeguards, dual-use systems create what security scholars call “surveillance creep”—gradual expansion from legitimate to questionable purposes without clear authorization or review.

Cross-Border Political Spillover

Cross-border political spillover compounds the risk. Surveillance in one state can affect regional dynamics: monitoring opposition figures who flee across borders, tracking activists coordinating regionally, or gathering intelligence during elections that has regional implications. When surveillance transcends borders without corresponding accountability frameworks, it becomes a transnational governance challenge.

The Regional Dimension

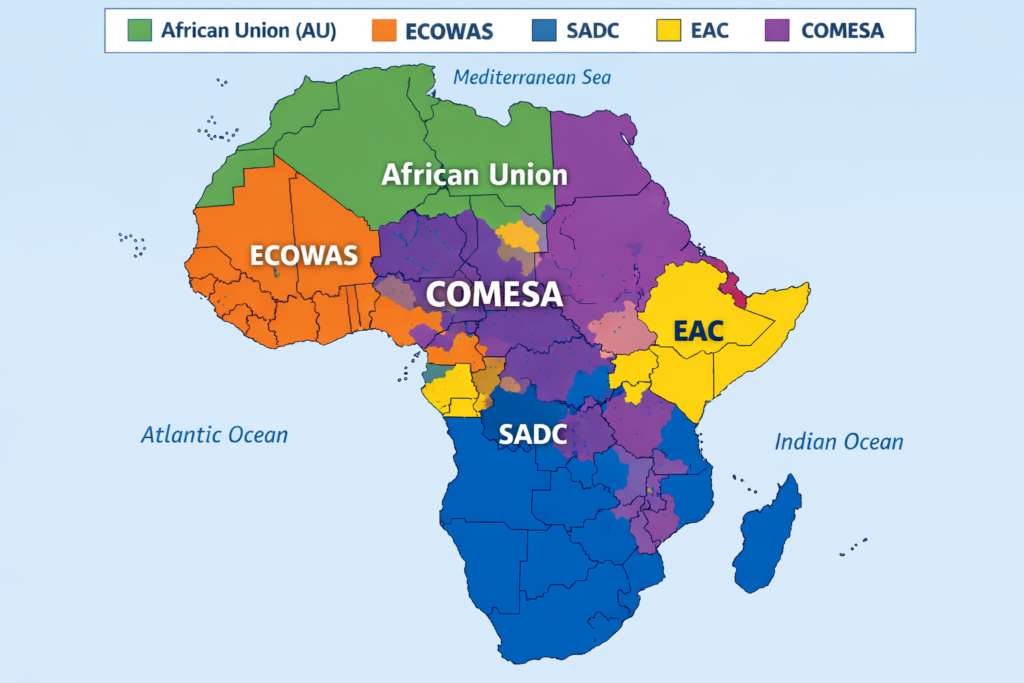

Map of African regional economic communities

Why This Is a Regional Problem

Surveillance doesn’t respect borders. Governance shouldn’t either.

African regions are economically, politically, and digitally integrated in ways that render purely national approaches to surveillance governance insufficient. Yet regulatory responses remain fragmented, creating three fundamental problems:

Cross-Border Data Flows Are Unregulated

Surveillance systems in Nairobi, Kampala, and Dar es Salaam increasingly share data for counterterrorism, border control, and law enforcement coordination. The EAC’s integrated security frameworks facilitate this cooperation—a positive development for regional security.

But there are no regional agreements governing data exchange standards—no harmonized rules for consent, retention, audit, or use. Data collected under Kenya’s relatively stronger protections can flow into Uganda’s weaker framework with no additional safeguards. This creates accountability gaps that undermine both security cooperation and civil liberties protection.

National Capacity Gaps Are Severe

Most African states lack the technical expertise to audit complex AI systems, the legal capacity to negotiate favorable contracts with major technology firms, or the institutional independence to investigate surveillance misuse. Small states are particularly vulnerable—lacking both leverage and expertise.

Regional institutions could pool technical capacity, creating centers of excellence that no single country could sustain alone. This is not unprecedented—Africa CDC coordinates pandemic response across 55 countries, the African Organization for Standardization harmonizes technical standards, and regional development banks pool financial expertise.

Vendor Leverage Exploits Fragmentation

Huawei, ZTE, and other major suppliers—whether Chinese, American, or European—negotiate country by country, customizing terms to each national context while maintaining technological control. No single state can demand fundamental changes to proprietary systems or credibly threaten to walk away.

But regional standardization—minimum procurement requirements, mandatory interoperability, shared data sovereignty rules—would shift bargaining power. Vendors would face a choice: meet regional standards or lose access to integrated markets.

Regional coordination is not just desirable. It is the only viable path to meaningful governance.

The Governance Gap: What’s Missing at the Regional Level

Regulatory Divergence Creates Race-to-Bottom Dynamics

Across Africa’s regions, surveillance regulation is fragmented. Countries within the same economic community have radically different standards:

- Authorization requirements: Some countries require judicial warrants for targeted surveillance; others allow police or intelligence agencies to activate systems at will.

- Data retention rules: Retention periods range from weeks to indefinite storage, with no regional consensus on proportionality.

- High-risk technologies: Facial recognition, predictive policing algorithms, and emotion detection software are deployed with no shared threshold for when these technologies require special authorization or independent review.

This divergence creates perverse incentives. Vendors will naturally gravitate toward the most permissive regulatory environments, and governments facing pressure to demonstrate security results will point to neighbors with weaker standards as justification. Without regional floors, national protections erode through competitive deregulation.

Political Spillover Undermines Regional Integration

Surveillance misuse in one state increasingly affects neighboring countries:

- Elections: Surveillance deployed during elections can monitor opposition figures who campaign across borders, or track diaspora communities politically active in multiple states.

- Freedom of movement: The EAC and ECOWAS guarantee freedom of movement, but surveillance systems can track and profile individuals as they cross borders, creating de facto restrictions without legal basis.

- Cross-border political targeting: Governments monitoring dissidents who flee to neighboring countries undermine regional asylum and refugee frameworks, turning surveillance into an instrument of transnational repression.

These are not hypothetical risks. Human rights organizations have documented cases of surveillance data being shared across borders to track political activists, with limited judicial oversight or reciprocal accountability mechanisms.

Sovereignty and Technological Dependency

The most profound governance gap is technological sovereignty—or its absence. Surveillance systems supplied by major technology firms typically involve:

- Software that cannot be independently audited: Proprietary code prevents governments from verifying what data is collected, how algorithms make decisions, or whether vulnerabilities exist.

- External control over updates: System upgrades and security patches come from foreign vendors, who can modify functionality without transparent disclosure.

- Limited local technical capacity: Few African states have the expertise to maintain, modify, or replace these systems independently.

This creates asymmetric dependency regardless of vendor nationality—whether Chinese, American, or European. Vendors can understand more about how systems are used than the governments that operate them. And when contracts expire, replacement costs are prohibitive—forcing governments to renew on unfavorable terms.

Regional coordination could change this dynamic. Pooled procurement across multiple states would increase bargaining power. Shared technical standards would reduce lock-in. Regional centers of technical excellence could train local experts and conduct independent audits.

Long-Term Fiscal Exposure

Surveillance infrastructure is increasingly embedded in sovereign debt. Financing models tie surveillance procurement to broader infrastructure loans, making it difficult to isolate costs or negotiate payment terms separately.

This creates fiscal risks: hidden costs compound over time as licensing and maintenance fees exceed initial deployment costs; exit costs are prohibitive, requiring not just new hardware but new software platforms, retraining personnel, and rebuilding institutional knowledge; and regional contagion is possible if debt distress forces renegotiation affecting integrated systems across borders.

Surveillance is no longer just a civil liberties issue or a security policy question. It is a fiscal and sovereignty issue with regional implications.

What Regional Bodies Can Do

Regional institutions have successfully harmonized policy before—on trade, health, infrastructure, and increasingly, cybersecurity. Surveillance governance is the logical next step.

Adopt a Regional Surveillance Governance Framework

The African Union, ECOWAS, SADC, EAC, and COMESA should establish binding minimum standards for surveillance systems, modeled on successful regional frameworks.

Core principles should include:

- Lawful purpose limitation: Surveillance must be authorized for specific, legitimate purposes (e.g., crime prevention, traffic management) and cannot be repurposed without new authorization.

- Proportionality and necessity tests: Systems must be necessary to achieve stated goals and proportionate to the risks addressed—mass surveillance for minor infractions fails this test.

- Independent authorization for high-risk uses: Facial recognition, predictive policing, and emotion detection should require judicial or independent oversight before activation.

These standards would not prevent surveillance. They would govern it. States could still deploy smart city systems for legitimate security and efficiency purposes, but within a framework of accountability that travels across borders.

Harmonize Data Protection Standards

Currently, some African countries have comprehensive data protection laws, others have weak or outdated provisions, and some have none at all. This fragmentation undermines regional digital markets and enables surveillance data to flow to jurisdictions with minimal safeguards.

Regional harmonization would:

- Align member states to baseline data protection principles—consent, purpose limitation, retention limits, and subject rights.

- Enable mutual recognition of data safeguards, facilitating legitimate data sharing while preventing regulatory arbitrage.

- Require cross-border data sharing agreements for surveillance data, specifying purposes, retention limits, and oversight mechanisms.

The AU Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (the Malabo Convention) offers a foundation, but adoption has been slow. Regional economic communities should accelerate implementation and build enforcement mechanisms.

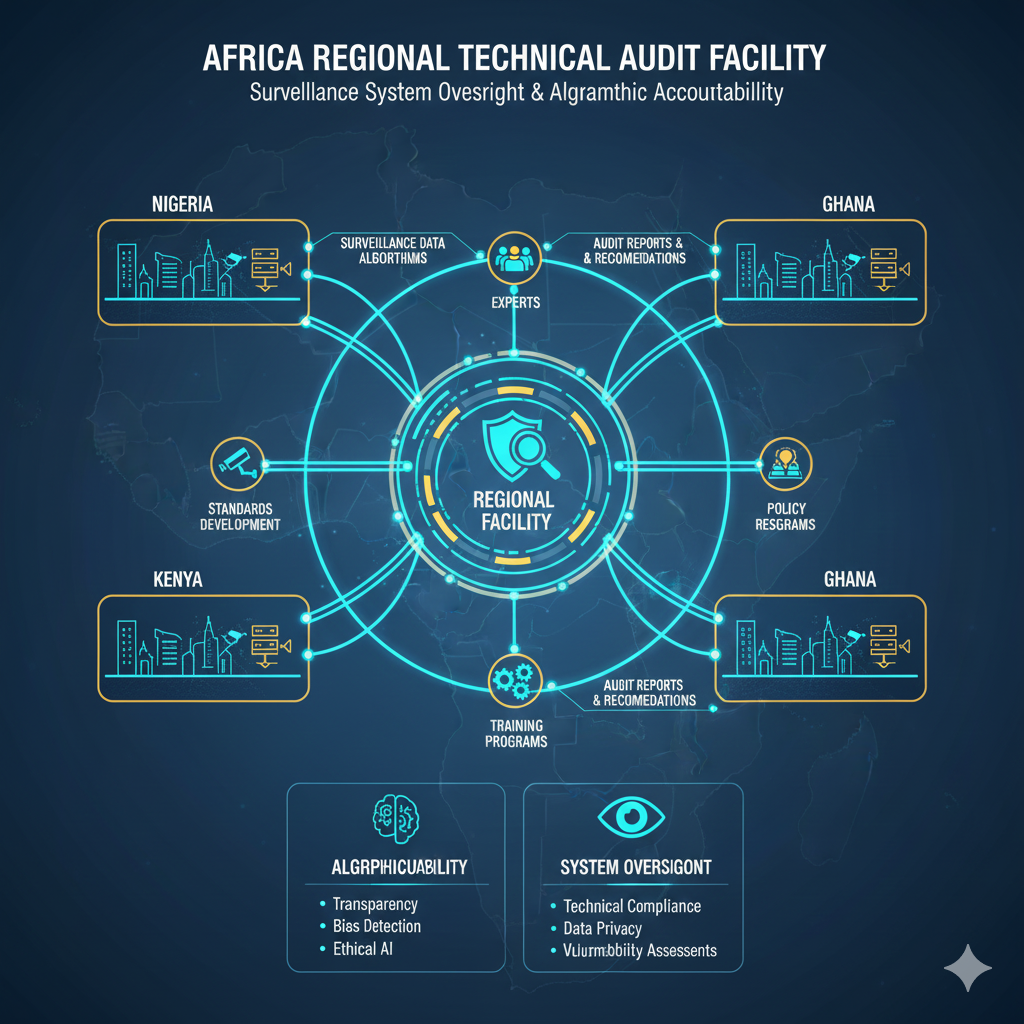

Create a Regional Technical Audit Facility

Most African states lack the capacity to audit complex surveillance systems—verifying what data is collected, how algorithms function, whether vulnerabilities exist, or how systems are actually used.

A regional facility could:

- Pool technical experts from across member states, creating a center of excellence that no single country could sustain alone.

- Conduct independent audits of surveillance systems, reviewing contracts, testing algorithms, and assessing compliance with regional standards.

- Provide technical assistance to governments negotiating with vendors, leveling the playing field in contract negotiations.

- Train national regulators and data protection authorities, building distributed capacity across the region.

This model exists in other sectors—regional disease surveillance centers, financial regulation authorities, and telecommunications regulators. Surveillance governance should follow the same logic.

Standardize Smart City Procurement Rules

Current procurement practices obscure surveillance within broader ICT projects, hide costs across multiple budget lines, and lock governments into long-term dependencies.

Regional procurement standards should require:

- Unbundling surveillance components: Separate line items for cameras, analytics software, and data storage, allowing scrutiny of surveillance-specific costs.

- Competitive bidding: Open procurement processes that prevent single-source contracts and enable alternative vendors.

- Disclosure of financing terms: Full transparency on loan conditions, licensing fees, maintenance costs, and exit clauses.

- Interoperability and exit clauses: Contracts must include provisions for transitioning to alternative vendors, data portability, and system transferability.

Standardizing procurement regionally prevents exploitation of weak national processes and gives governments collective leverage regardless of vendor nationality.

Protect Elections and Political Processes

Surveillance during electoral periods poses particular risks—monitoring opposition campaigns, tracking voter behavior, or intimidating activists. Yet few African countries have specific safeguards for election-related surveillance.

Regional bodies should establish:

- Prohibition on surveillance use during elections without independent oversight: Electoral management bodies or courts should authorize any surveillance related to elections.

- Ban on political profiling via smart city systems: Systems cannot be used to track political affiliations, predict voting behavior, or target campaigns.

- Rapid-response review mechanisms: Independent bodies that can investigate surveillance complaints during electoral periods and issue binding decisions.

The AU and regional bodies already monitor elections. Adding surveillance oversight to these mandates is a natural extension.

The Path Forward

Strategic Framing: This Is Not Anti-China, It’s Pro-Governance

The debate is often framed incorrectly—as China versus the West, or as a choice between development and rights, or as technophobia versus modernization.

The real question is: Can African states adopt smart city technologies without importing surveillance authoritarianism?

This is not an anti-China agenda. It is a pro-governance agenda. China is not the only exporter of surveillance technology—American, European, and Israeli firms also operate across the continent. What makes Chinese systems particularly consequential is their scale, integration, and the financing models that accompany them.

But the deeper issue transcends any single vendor. It is about whether technology deployment will continue to outpace accountability, or whether governance will catch up.

Why Regional Coordination Makes Sense

Surveillance technology is now a regional public policy issue, comparable to financial regulation, trade standards, and cybersecurity. African regions have successfully coordinated on all of these.

Consider precedents:

- Trade harmonization: Regional economic communities established common external tariffs, standards recognition, and dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Health coordination: The Africa CDC coordinates pandemic response, vaccine procurement, and disease surveillance across borders.

- Infrastructure planning: Regional bodies coordinate roads, railways, energy grids, and telecommunications networks.

Why should surveillance infrastructure—more consequential for civil liberties and political stability than any of these—remain uncoordinated?

Without regional action, Africa risks embedding uneven digital governance into shared markets and mobility frameworks. Surveillance will become a tool of control in some states and a protection mechanism in others, with citizens’ rights depending on which border they cross.

Governance Must Catch Up—Regionally

The cameras are up. The systems are live.

The question is: who is watching the cameras?

And the answer must be: African institutions, empowered regionally, accountable democratically, and sovereign technologically.

In Nairobi, Addis Ababa, Kigali, Lagos, Johannesburg, and dozens of smaller cities, surveillance infrastructure shapes daily life. Traffic is managed more efficiently. Emergency response times have improved. Crime detection capabilities have advanced. These benefits are real and measurable.

But so are the risks—selective targeting, political control, technological dependency, and fiscal lock-in. These risks are not hypothetical. They are documented, growing, and increasingly transnational.

The Choice Ahead

The next phase of Africa’s digital future will be decided not by who installs the technology—but by who governs it, and whether that governance happens state by state, or region by region.

Fragmented national approaches create weakest-link vulnerabilities, enable vendor leverage regardless of origin, and undermine the civil liberties gains that many African states have fought for over decades. Regional coordination is not a luxury. It is a necessity.

African regions have the institutional capacity to act. The African Union, ECOWAS, SADC, EAC, and COMESA have coordinated complex policy before. They can do so again.

The infrastructure is already in place. Governance must now catch up—regionally.

The alternative is a continent where surveillance infrastructure determines political possibilities, where citizens’ rights depend on which border they cross, and where technology vendors—regardless of nationality—hold more power over African cities than African governments do.

Next Steps for Stakeholders

For Regional Bodies: Commission technical feasibility studies on regional surveillance governance frameworks. Initiate consultations with member states on minimum standards. Build on existing digital rights commitments in the Malabo Convention.

For National Governments: Audit existing surveillance contracts for compliance with emerging regional standards. Assess capacity gaps that regional support could address. Engage in regional coordination dialogues before the next procurement cycle.

For Civil Society: Document surveillance practices through systematic research. Build cross-border networks to share evidence and strategies. Engage regional institutions on norm-setting and accountability mechanisms.

For Development Partners: Support regional technical capacity building. Fund independent audits and algorithmic accountability research. Align assistance with governance-first approaches that strengthen institutional oversight.

For Technology Providers: Demonstrate commitment to governance by offering transparent procurement terms, supporting local capacity building, and accepting independent audits. Regional markets reward accountability.

The time to act is now—while systems are still being built, before lock-in becomes irreversible, and while African regions still have the agency to shape their own digital futures.

The surveillance boom happened quietly. Governance must happen deliberately, transparently, and regionally.